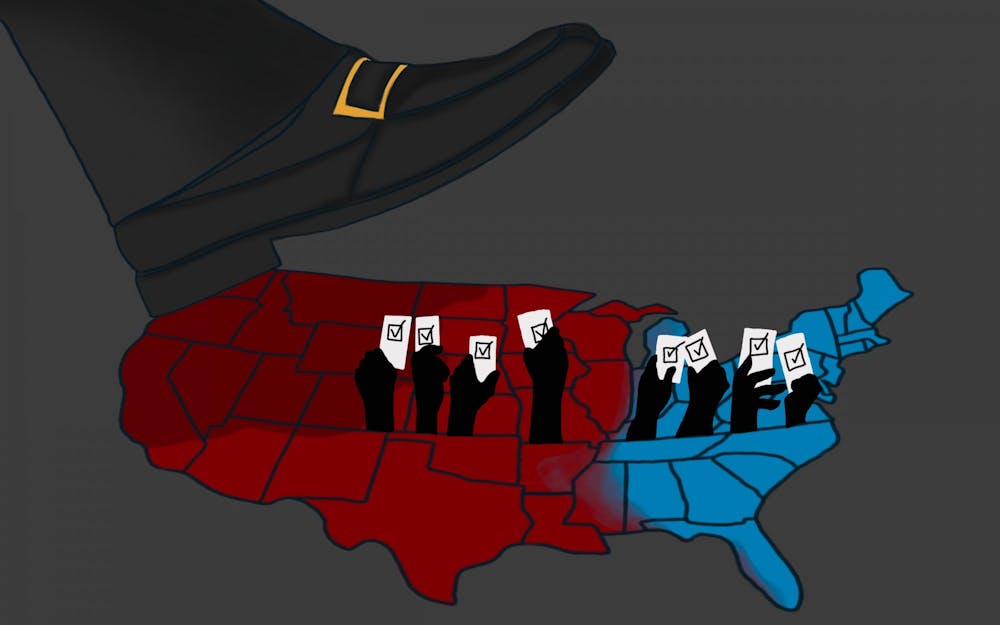

For every law placing an undue burden on voting, the foundation of democracy crumbles. The United States has a long and cruel history of disenfranchising voters of color with no end in sight. Just last week, Black Georgia Rep. Park Cannon was arrested for knocking on Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp’s door as he signed oppressive voting legislation into law.

During the 2020 elections, people of color and young voters turned out in record numbers to put Democrats in control of Congress and the Presidency. Now, Republicans across the country are retaliating. Indiana — a state notoriously known for its voting suppression — is witnessing the same.

More than 250 bills with restrictive voter language have been filed across 43 states as of Feb. 19, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Indiana is included twice on the list thanks to SB 353 and SB 398. Both bills would make it more difficult for voters to cast their ballots, whether through strict absentee ballot standards or by requiring proof of citizenship at the voting booth.

Indiana is not new to the practice of voter disenfranchisement. The Hoosier state has a long history of implementing restrictive voting laws, such as a strict photo ID policy and one of the earliest voter registration deadlines in the U.S., allowing those in power to depress turnout among communities of color. Indiana even purged 28.7% of its voters between 2016 and 2018 with “Crosscheck”, a flawed software utilizing the illegal practice of purging voters after inactive two cycles without notice.

The horrific trend of voter disenfranchisement continued through the 2020 general election as Indiana was one of four states to require an approved reason to vote by mail. The COVID-19 pandemic was not a valid excuse.

Because of restricted absentee ballot access, Elizabeth Elliott, an IU student from Indianapolis, waited in line for nearly seven hours to vote at Krannert Park Community Center, a Marion County early voting site. Unfortunately, not everyone has the privilege of waiting hours upon hours to vote.

Related: [New voter outreach organization aims to get more Indiana voters registered, verified]

“I definitely saw people leave, and I saw people leave and come back,” Elliott said. “I saw people pick up their kids from daycare and come back. I saw people call their work and say that they had to call off that day and you know, I don't know what type of sacrifices that means for them.”

Unsurprisingly, Indianapolis dealt with the brunt of long lines due to numerous voting barriers. Not only is it one of the most Democratic areas in Indiana, it’s also diverse with vibrant Black and Brown communities. A 2020 Brennan Center for Justice study reported that Black and Latino voters were more likely to wait longer than their white counterparts, compounding on existing barriers to voting access.

Bloomington dealt with similar wait time issues as lines ranged from one to two and a half hours long at the sole early voting location. Expanding early voting sites is an obvious yet complicated solution. Unfortunately, new locations require the unanimous consent of the bipartisan county election board. Republicans can and will block voting expansion in democratically held counties, such as Marion and Monroe, for their own benefit.

The struggle for voting rights isn’t without its fighters at the Statehouse. State Sen. Fady Qaddoura, Indiana’s first Muslim lawmaker, bore witness to the Indiana Republican Party’s negative impact on voting rights. As Qaddoura walked the early voting line every day from 8 a.m. to nearly 10 p.m. at St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, a Marion County early voting site, he watched as voters waited anywhere from three to eight hours.

“I want Democrats and Republicans, and every person who is unaffiliated, to have the right to vote without any barriers,” Qaddoura said.

Expanding voter registration, early voting and absentee voting are all policy proposals other states have successfully implemented to increase voter access. Yet, the Republican supermajority at the Statehouse and other structural barriers make it difficult to actualize real change.

Conservatives continually use Indiana as an experiment to push the limits on disenfranchising people. If Republicans lawmakers wanted to remove voting access from out-of-state students or felons, what would stop them?

“We should do better and we should reform the way that we do elections, the way that we draw our districts, not to benefit any specific class or cohort of politicians, but rather protect democracy for generations of Hoosiers to come,” Qaddoura said.

Democracy is only as strong as its weakest link and it demands the best of us to fight for the future. Voter disenfranchisement is a dark, never ending pit, and Indiana will fall deeper into it without strong foundations to protect the rights of voters.

Alessia Modjarrad (she/her) is a junior studying economic consulting and law and public policy. She is the president of the College Democrats of Indiana and works as a political operative on various Democratic campaigns