I sat in AP U.S. history class my junior year of high school during the lesson on the civil rights movement and the years following it. I had cautious optimism the history teacher might get it right this time, despite being a white man.

The last and only time I had a Black social studies teacher was in eighth grade. His name was Mr. McDaniel. He was tall and skinny, and he always wore khakis with a bright-colored collared shirt. Except for Fridays, when he wore a running T-shirt — he was also the track coach. Mr. McDaniel always taught history in a way that felt real, not watered down. He was funny, yet always seemed to teach history the right way.

The correct way.

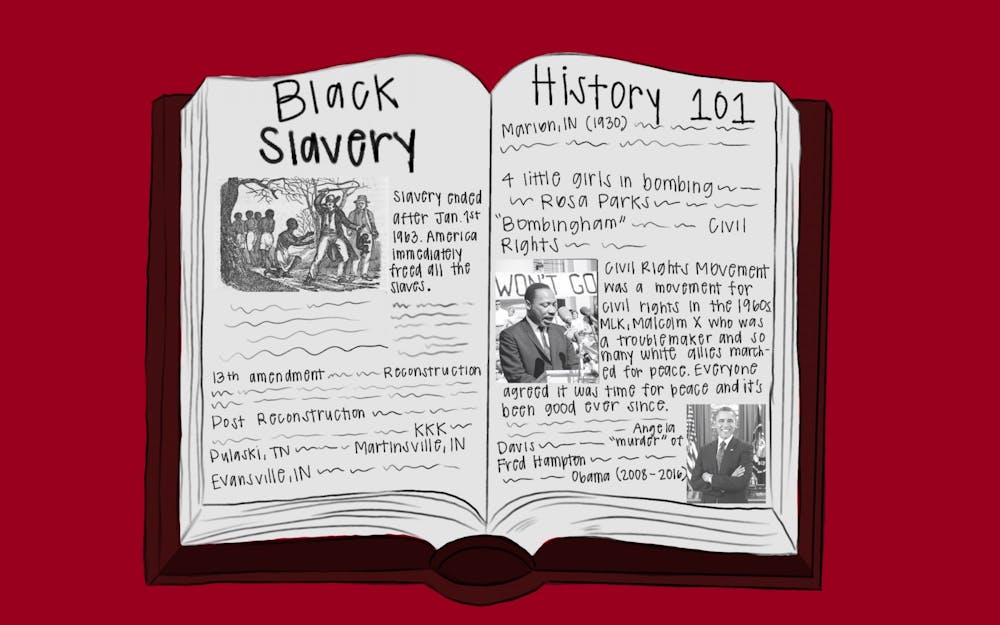

I sat in the front right corner of that class in 2015, reading the “McGraw Hill American History” textbook that made it seem like after Martin Luther King, Jr., all of the systemic racism in the world was suddenly fixed. That is not possible.

The history book had a picture of former President Barack Obama after he won the election in 2008. The context made it seem like racial inequalities in America were fixed in the blink of an eye. The election of Obama was viewed as the end of racism and the beginning of a colorblind society.

This narrative is incorrect and harmful.

That civil rights unit in high school was not the only case where I had had an off-setting feeling in my stomach about how history was being taught. When we talked about slavery in elementary through high school, we really only touched on the fact that enslaved people were taken from Africa, brought to America for their free labor and were whipped.

While all of those facts are true, what about the rape of Black women by their slave masters? What about the countless Black men and boys who were lynched by white mobs?

A 2018 study by the Southern Poverty Law Center, titled “Teaching Hard History,” found only 8% of high school students could identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War. Only 46% knew what the Middle Passage was, and 32% knew which amendment formally ended slavery.

Textbooks do not do an adequate job of teaching history. According to a rubric created by the Southern Poverty Law Center, the average score calculating the number of textbooks properly covering slavery was 46%. The rubric included 10 categories, such as causes of the Civil War and the effect slavery has on contemporary racism. For each category, the textbooks analyzed were given a score from 0 to 3 — 0 being no coverage and 3 being in-depth coverage. The highest score was 70%. The United States was built on the backs of slaves, but history books rarely reflect this reality.

My grandmother had always been an avid history-teller. She would often sit around the living room with my sisters and me, informing us of the hardships she went through as a Black woman growing up in the 1960s. She marched in Washington, D.C. to fight to have Martin Luther King, Jr. Day recognized as a national holiday. This always reminded me that I’m not so far removed from the history many perceive as long ago.

I was 12 years old when I first realized that supposedly long-ago history was still going on today. Trayvon Martin was killed on Feb. 5, 2012. That day, I felt sick to my stomach. That was my first time seeing and understanding how inhumane someone could be treated because of the color of their skin. My eyes were glued to the news in the following weeks. I read articles and educated myself on the killing, and on what it meant for America.

One hot humid day during the summer of 2013, I was sitting in my neighbor’s house waiting for the verdict for George Zimmerman, Martin’s killer. I sat anxiously on the edge of a worn brown leather couch. The house was full of the smell of cigarettes, and my eyes were glued to the television. In my 21 years of life, that was one of the few times where I remember what all five of my senses felt in a particular moment. The memory still feels eerily vivid.

Not guilty.

My stomach turned. My heart started racing. My hands were sweaty. I could not fathom the hate — but as a preteen, I truly realized just how devastating racism is in America. And I knew I wanted to do all I could to make a real difference.

[Related: OPINION: Black men should not be forced to be martyrs]

While African American and African Diaspora studies courses have provided me with a formal education, they also provided a real-world look into a lack of attention paid by education systems to Black history.

Coming to college, I wanted to be intentional about educating myself more on Black history. I always knew I wanted to make an effect in diversity, equity and inclusion — and immersing myself in Black history would aid in doing that by increasing my knowledge on the history of race. If I was not intentional, it would not happen, because the education system is set up to ignore Black History.

When I started my freshman year at IU, I declared a minor in AAADS. The department focuses on exploring facets of African-American and African people through a variety of lenses including politics, sociology, history and literature. The courses combine historical and current events to create meaningful lessons on Black people and those of African descent.

But I ran into a problem. I typically had difficulties signing up for courses in the department. They were either unavailable or full.

Toward the beginning of college, I was able to sign up for courses without difficulties, but that changed around the end of my sophomore year. For the minor, 15 credit hours are required, with nine in a specific concentration. That doesn’t sound too hard, right?

To complete the minor, a specific literature course, AAAD-A 379, Early Black American Writing, is required. But it was not offered every semester I tried to sign up, and the class quickly filled up. I panicked because I was not sure when I was going to be able to take it but knew I needed to.

Each semester I tried to sign up to take the class, it was full, and I often attempted to get on the waitlist. I was never taken off the waitlist, so I knew I had to take matters into my own hands to figure out how I could complete my minor with the least amount of stress possible. There is clear value in the class, and I wanted other students and myself to be able to have it.

In an interview with the Indiana Daily Student in March, Valerie Grim, director of AAADS undergraduate studies and professor of AAADS, explained struggles and successes in the department.

[Related: Black Voices: More professors needed in African American and African Diaspora Studies department]

In March, Grim told the IDS the department needs more funding to build strong programs and attract and support more students and faculty.

Grim also said the department needs more faculty listed only in the AAADS department. If this happens, there would be less division of faculty and improvements in the number of credit hours taken in the department, which would support increased funding.

In the past decade, the number of AAADS majors has averaged 13 students in the undergraduate program, according to data from College of Arts and Sciences Executive Dean Rick Van Kooten. This year, there are 13 undergrad students pursuing the minor. AAADS department Chair Carolyn Calloway-Thomas said she would like to see more than 100 students majoring or minoring in the department in the next year, according to the article.

I was nervous as I went to the eighth floor of Ballantine Hall, about to speak to Grim about the situation with my minor. I knew I had to be assertive but did not want to come across as complaining because I really do enjoy what I am able to learn through the program.

Grim, the program director, welcomed me into her small, office lined with bookshelves filled with history books. She was incredibly welcoming, and made me feel like I could be open.

When I took my backpack off and sat in a chair next to her computer in the office, Grim asked how I was doing and how she could help. After discussion, she informed me it is not uncommon for students to have to make changes to their course work to fulfill the major or minor.

Although I was slightly relieved I was not being a total inconvenience, I was concerned that so many other students struggle with the same situation as I did.

Grim said I was able to use a different course I had already taken, AAAD-A 249: African American Autobiographies, to fulfill the requirement instead.

While I, too, would like to see 100 many people with the major and minor, I struggle to understand how that could be possible, informed by my own difficulties signing up for classes.

African American Autobiographies, the class that replaced Early Black American Writing for me, changed my perspective on history and how real the brutalities on slavery are in America. I knew slaves were treated horribly, but the grave inhumanity of the captors struck me in a deeper way than ever before.

I was sitting in my African American Autobiographies course at 9 a.m. in 2018 and I was tired, especially after the 20-minute walk from my dorm. But I was ready to learn. In the class, we usually read novels about historical figures from the Black community such as Frederick Douglass and Maya Angelou.

The day’s reading assignment — direct accounts of enslaved peoples experiences on the trans-Atlantic slave trading routes — is one of few very specific moments sitting in a classroom I will never forget.

One account was about a woman who gave birth on a ship floor. The floor was covered in fecal matter, vomit and decomposing bodies. She was alone, yet bonded with the others on the ship, who were feeling the same pain and suffering as she was. After she had the baby, it was thrown into the sea by a captor. The baby could not provide physical labor, so it meant nothing to the captors, who I struggle to call people.

The rest of class, I felt sick to my stomach. My mind could not fathom the pain, nor how someone could do something so inhumane. I was usually one to participate in class, but I was silent for the remaining 30 minutes. I could not articulate anything. I could only feel pain for my ancestors.

“Black Panther” came out my freshman year of college, during the same semester I took the class. At the end of the movie, there was a scene where Killmonger, the movie’s antagonist and cousin of the Black Panther, said, “Bury me in the ocean, with my ancestors that jumped from the ships, because they knew death was better than bondage.”

Sitting in the movie theater, I thought back to that class and wondered if I would be strong enough to choose life if I were on a ship, knowing I was going to be sold and tortured. It made me feel for my ancestors. Do I have a relative who chose the sea?

That class proved to be the power in the AAADS department. I felt more connected to my ancestors — like I had a glimpse into their pain, and ultimately their sacrifice that allowed me to even be sitting in that class, at a university. While most of me felt lucky to have all of these opportunities they did not, another part of me felt unworthy.

I likely had ancestors who were slaves. They could have been on these ships, watching their family members be sold away to other plantations. Yet here I was, taking a class at a prestigious university. They gave the ultimate sacrifice, and I will never really be able to put into words what that means to me.

There is power in knowing the often undermined truth. While this issue may seem subtle, the lack of accessibility to classes like this AAADS course comes down to systemic problems within society. People are so used to thinking this watered-down version of history is the truth, they do not even realize it is wrong. This is still a form of racism.

Summer 2020 served as a great awakening for many people who had not recognized the racial injustice that plagued the United States before. While the racial awakening is a positive development, one question keeps circulating in my mind: What took so many people so long to understand?

On May 13, 2020, I published a column for the IDS titled “Black men should not be forced to be martyrs.” I was completely unaware of what was about to take place less than two weeks later. In the column, I mentioned a powerful quote from a poet, Jasmine Mans: “My son will not be a martyr for a war he never asked for.”

George Floyd unwillingly became a martyr May 25, 2020. His death in itself proves the cyclical nature of the war against Black Americans. It should not take people dying for people to understand the racism that is deeply ingrained in America and the devastating effects it has on the Black community. It should not take a man being murdered on camera for someone to realize racism exists in America.

[Related: Black Voices: Chauvin is guilty. But George Floyd can’t come back.]

A way to allow people to recognize the atrocities sooner is through proper education. In order for people to receive proper education and know the truth, classes must be offered and available for students to take. Programs such as AAADS are critical in educating the community on the realities of life for Black Americans since the slaves were first brought to America from Africa in 1619.

But these great programs aren't enough if you can't enroll in them, and it's even worse in places where these don't exist.