We’ve all heard of Woodstock – a music festival during the Summer of 1969, when hippie culture was at its peak and artists such as the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane and Jimi Hendrix graced the stage. Marketed as “3 Days of Peace & Music”, Woodstock is considered a crucial marker in American music history.

However, did you know another monumental event in music history took place during that same summer, just 100 miles away?

The Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of six free concerts held in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park, sometimes referred to as “Black Woodstock” according to Rolling Stone, was a crucial moment in the history of Harlem, the Civil Rights movement and Black culture. Yet, it was largely forgotten until recently.

“Summer of Soul (...Or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)”, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s recently released documentary, captures this missing piece of history.

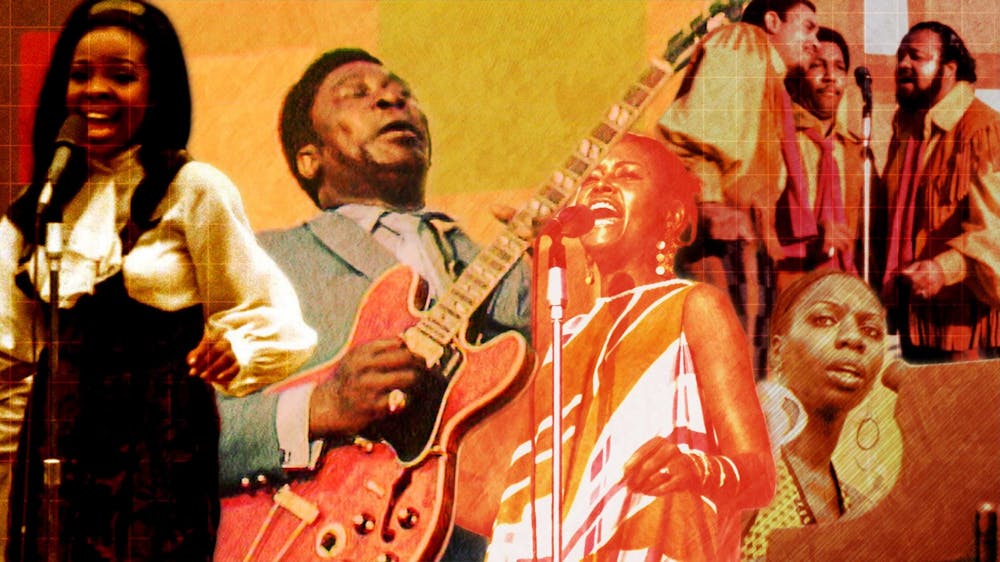

Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, Nina Simone, Sly & The Family Stone, The 5th Dimension, Gladys Knight & The Pips and The Staples Singers were some of the many artists the festival featured. Around 300,000 people collectively attended the concert series, according to Rolling Stone. “Summer of Soul” masterfully portrays the Black community through present-day interviews with festival attendees and performers reflecting back on that summer.

The timing of the event was pivotal. As the documentary points out, the festival occurred as Americans mourned the loss of influential figures in the Civil Rights movement including Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

The festival served as a moment to recognize these tragedies, but also celebrate the Black community and foster Black pride.

One detail I found particularly powerful about the recordings of “Summer of Soul” was the multigenerational audience. While the star-studded lineup was impressive, it was clear people weren’t just there for the music. The festival symbolized something greater.

In the documentary, artists like Stevie Wonder, Marilyn McCoo and Gladys Knight reflected on the importance of truly connecting with the audience. They recognized how important the festival was during that time in history when many changes and movements were occurring in American society, one of these accomplishments being the moon landing.

The festival’s footage portrays audience members describing the moon landing as a less urgent matter when considering the issue of poverty in America, specifically among African-Americans.

As far as favorite performances, it's impossible for me to choose. From Stevie Wonder’s performance to Nina Simone’s, the festival’s energy remains constantly electric, with the charismatic direction of the festival’s coordinator, Tony Lawrence.

A stand-out moment in the documentary for me is Mavis Staples’ and Mahalia Jackson’s rendition of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” MLK’s favorite song. Vocalist Staples is interviewed and discusses the moment when one of her role models, gospel singer Jackson, asked her to help sing this ballad.

The power and emotion these women bring forth is indescribable. Sitting in my rough upholstered chair at the Classic AMC Bloomington 12 theatre I was transported. Their voices sent shivers down my spine and brought tears to my eyes.

It’s upsetting that something so great could be neglected for 50 years, unknown. I am grateful that filmmaker Hal Tulchin’s tapes of the festival, which sat in a basement for all this time, have finally been discovered.