This is the third column in a weeklong series celebrating Banned Books Week, which celebrates the freedom to read. Each column will review a different frequently challenged book.

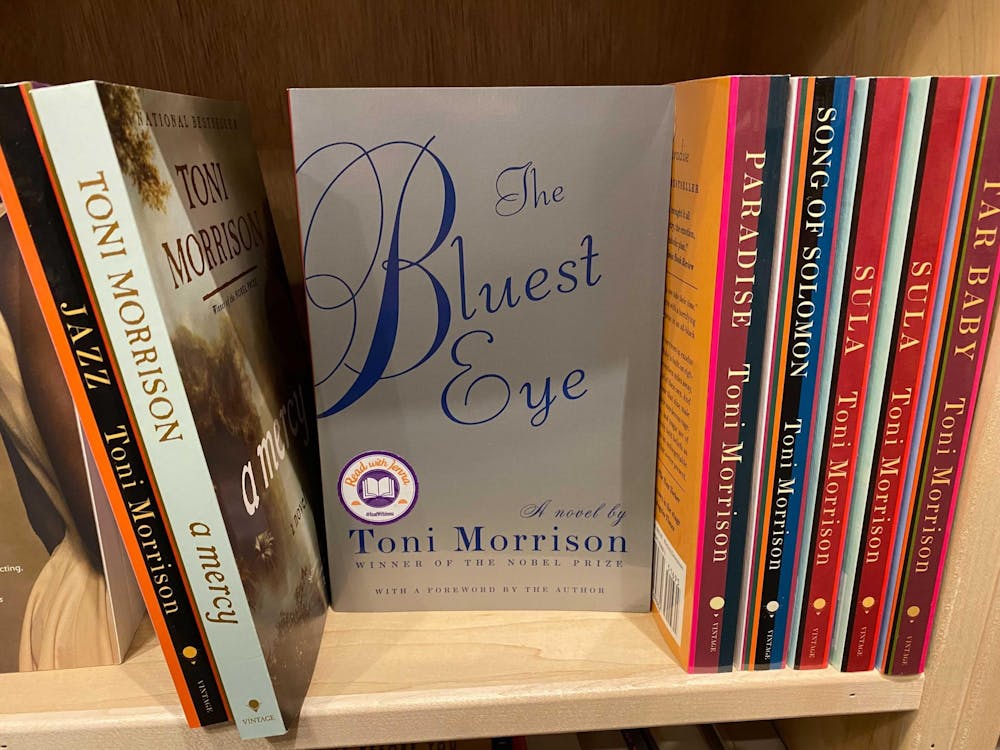

“The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison ranks high on my list of admirable writers because her style doesn’t remind me of anyone else’s. But because of that, she brings another notable female writer’s words to mind.

“One sees more intensely afterwards; the world seems bared of its covering and given an intenser life,” Virginia Woolf writes when discussing books she finds important in her work, “A Room of One’s Own.”

Woolf’s words clutter my head every time I finish reading Morrison’s prose. Her writing is so practiced and her stories so cutting it genuinely feels like a reader perceives the world more intensely at the conclusion of her work.

“The Bluest Eye” is Morrison’s first novel, published in 1970 and still landing on last year’s Top 10 Most Challenged Books list according to the American Library Association Office of Intellectual Freedom.

The novel covers reprehensible actions worth banning — namely incest and assault — but the story itself doesn’t deserve to be. Morrison expertly juggles different facets of characters while maintaining a central voice to make the narration cohesive. And that’s just the beginning of the praise this work warrants.

It tells the story of Pecola, a young Black girl growing up in 1940s Ohio, over the course of four seasons. Readers see the pervasive influence of racism in characters’ psyches, and Morrison adds a story about complex Black characters to a Western literary canon that too often lacks proper representation.

My experience with Morrison’s work has dealt with uncomfortable topics, but that doesn’t mean we should stop reading them. Fiction is about expanding our consciousness, and there is no one who does so better than her.

Morrison is widely recognized for her ability to comment on racial pain without sacrificing the inclusion of joy. “The Bluest Eye” fits firmly into this skillset.

Her stories are evocative, her word choice intentional and I can’t read her work without a pen in my hand to annotate. Her commentary on the craft of writing often covers the idea of words as a vehicle or as a menace, tools left up to the author to decide direction.

She manipulates words brilliantly in “The Bluest Eye,” beginning the first chapter with a play on the classic Dick and Jane story, a device she echoes throughout pages to juxtapose a stereotypical happy childhood with what it means to grow up as a young Black girl in a violent family in the 20th-century Midwest.

My Norton Anthology of Literature by Women, the collection which houses my copy of “The Bluest Eye,” prefaces the story by noting an early review it received. It “responded to the metaphorical richness of (“The Bluest Eye”) by explaining that it is as much ‘history, sociology, folklore, nightmare, and music’ as it is fiction.”

Morrison exists as a model in each field.