Editor’s Note: This column includes descriptions of sexual violence.

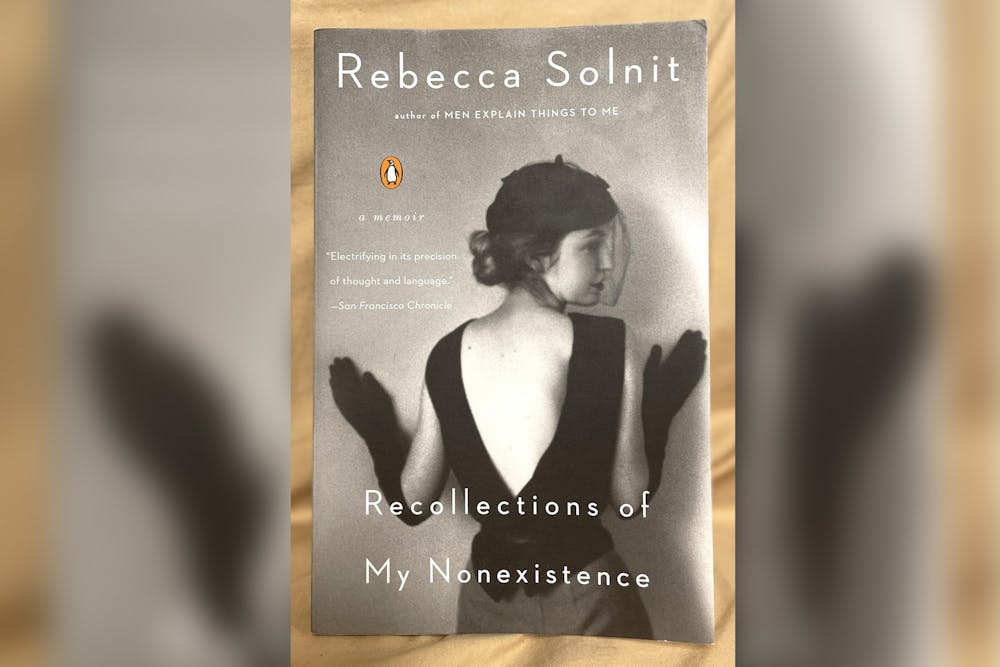

In her 2020 memoir “Recollections of My Nonexistence,” Rebecca Solnit describes womanhood as constant war.

Navigating our bodies, minds and souls in relation to external forces is like fighting our way through a minefield. With every footstep comes the possibility of annihilation.

The annihilation can be physical. It can take the form of a man robbing you of your autonomy and invading your body as though it is not your own. As Solnit writes, “What is rape but an insistence that the spatial rights of a man, and by implication men, extend to the interior of a woman’s body.”

The annihilation can be psychological, too. It’s carrying the burden of all the women before you who were subject to the insistences and aggressions of boyfriends, husbands, fathers, brothers and strangers on the street. It’s the moment when a man gets in your face, or yells, or calls you a bitch and some small part of you recoils in a way that feels primally feminine but has been insidiously conditioned since birth.

Solnit equates this way of life to a shade of “nonexistence.” As women, she argues, we constantly walk the line of existing enough for men to realize their own sexual pleasure and virility, but not existing too much as to offend or monopolize a space that was never meant for us.

Solnit’s story is not one of victimhood, but rather coming to terms with her place in the world and liberating herself in spite of a culture that seeks to confine. With warmth, profundity and lyricism, she illuminates the universal oppressive experiences among women while celebrating the freedom she found in life on the margins.

In her ruminations, Solnit continuously lays bare the personal experiences of women that are silenced and, if acknowledged at all, explained away.

Attractiveness and beauty standards are just one manifestation. If a woman is attractive according to the rules of heteropatriarchy, she is a potential conquest. She is vulnerable to harassment or worse. If she is unattractive according to heteropatriarchy, she is derided or ignored altogether.

Solnit’s particular talent lies in her examination of language, culture and media. Her prose winds and bends, a kind of protest to masculine demands for economy of words.

She also challenges media representations of women and the effects on the psyche. Film, TV and books often fetishize violence against women as a form of eroticism, self-actualization or aestheticism, from Quentin Tarantino to Edgar Allen Poe to Alfred Hitchcock, Solnit writes. Historically and even contemporarily, women rarely identify with the protagonists of stories because they are so often told through the lens of a man.

Though it is a frequently dark story, “Recollections of My Nonexistence” is ultimately a path through self-discovery. Solnit finds herself in the American West and through writing about environmentalism, feminism and the refuge she found in communities on the fringes.

Her memoir rejects what we are told is central and what is peripheral. Women are not damned to eternity as the muse and never the artist.

It is also wonderfully sincere, despite all the opportunities life has given her to be ironic and detached.

“It would take me a long time to understand what a limitation cleverness can be, and to understand how much unkindness damaged not just the other person but the possibilities for you yourself, the speaker, and what courage it took to speak from the heart,” Solnit writes.

Solnit advocates for saying what you mean loudly, without apology and without the armor of cynicism. It is a message not just for women, but for every community that has been marginalized and for every person who feels silenced.