In an operatic world full of dramatic characters, iconic tropes and theatrical stereotypes, Monteverdi’s early Baroque masterpiece “The Coronation of Poppea,” or “L’Incoronazione di Poppea” in Italian, still manages to distinguish itself from the others.

This show is a 1600s-era take on the doomed historical figure of Poppea, wife of the infamous Roman emperor Nero. The opera depicts Poppea’s cold-blooded scramble for power. Interestingly, it does not actually show her downfall but rather ends on a successful note for her with her coronation as empress, with the audience left to discern the irony on their own.

Monteverdi’s last opera is a testament to the incredible innovations he brought to this art form. While much of the music may not sound particularly experimental to our modern ears, it broke the rules of form and harmony when it was written. Monteverdi emphasized emotions and expression above all, and with each careful phrase, this sensitivity shone through in the recent dress rehearsal at the Jacobs School of Music I attended this week.

There is an almost delicate feeling to some of the subtleties present in the work, something that was very effectively brought out in this particular performance.

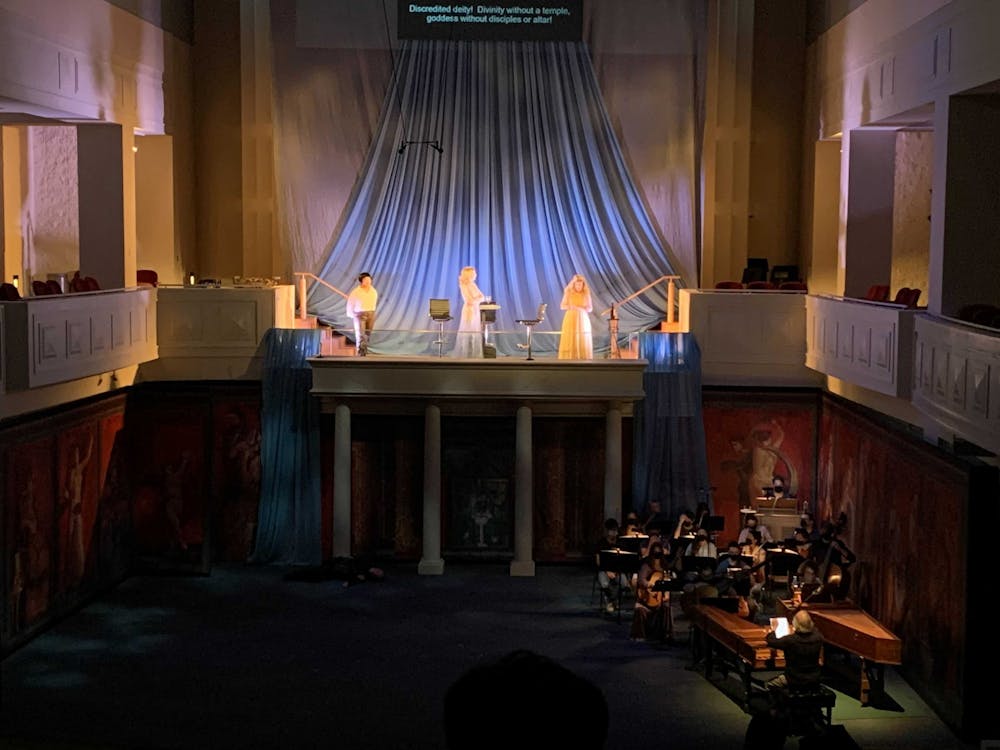

It was staged in Auer Hall, which is smaller than the Musical Arts Center auditorium where many other operas are often staged on campus. While ancient Roman-style paintings graced the edges of the stage, none of the scenery felt overly intrusive or detailed.

The instrumental ensemble was placed onstage, as opposed to in an orchestra pit, resulting in an intimate musical collaboration with the singers performing right next to it.

For much of the performance, the audience almost felt like an intrusion. Characters spied on each other from behind columns and gave introspective monologues from a balcony while the instruments strummed in mournful accompaniment. Deities peeked on the mortals down below them.

A surprising number of scenes took place in private chambers or alleyways as opposed to grander settings. There were never more than a handful of characters on stage, many of them singing their inner thoughts rather than participating in dialogues. The audience often saw Poppea in her most private moments of scheming rather than in a political arena.

In doing so, this production seemed to stay close to Monteverdi’s original intent in refusing to simply offer a morality tale but rather a nuanced and intimate portrait of a tormented character consumed with ambition. It is telling that the opera ends with a tender love duet between Poppea and Nero rather than a grand chorus.

As old as the opera and the historical figures may be, the persistently thought-provoking ideas and timeless beauty of the music were clearer than ever before in this production.