Editor’s Note: This article includes mention of sexual assault.

On top of the stone wall at Seminary Square Park sits a coffee and breakfast station: a percolator full of hot drip coffee, a container of hot water for tea, a stack of styrofoam cups, Mini Muffin pouches and a bottle of hand sanitizer.

Heather Lake wakes up early to brew the coffee, which takes about 30 minutes. While she waits, she hopes that it will be a good day, that she’ll get to have a good conversation with friends, that she could help someone.

She boils the water for tea, grabs creamer and sugar and loads it in her car. Then she takes it over to the park, arriving at around 9:30 a.m.

Gordon, a member of the unhoused community, bobs a teabag up and down in a cup of hot water. He’s glad to have a hot drink.

He and others in the park gave Heather her nickname: “The Coffee Lady.”

The park is a place he goes to grab a drink and a snack. In the wintertime, he said Heather brings donated scarves and gloves, and last summer she brought cases of water purchased with her leftover food stamps. Heather is there for those who need it, he said.

“She was being really generous,” he said. “She had more than she needed, so she shared.”

Heather, 52, has made her rounds during her coffee hour in Seminary Park since last year, when the pandemic combined with Indiana winter conditions motivated her to provide extra sustenance to the unhoused community.

There’s a sense of community within the park: talking, laughing, cracking jokes. Heather and the others in the park talk about their week, catching up on what’s happening in their lives.

Heather said she sees everyone as her equal. She gives hugs and exchanges recipes. She calls the people she’s known the longest her friends because that’s what they are.

For a moment, it’s easy to forget the people are not there just to socialize or get a free morning cup of coffee. They are unhoused, spending their days in the park.

When she visits the park, she’s helping people in a situation that was once her lived experience.

Heather graduated early at 16 in Kansas City, Missouri, and was accepted into University of Missouri - Kansas City. However, she said she wasn’t emotionally ready for college and failed out of her freshman year.

With an absent father and a sick mother, Heather said she was unable to go back home. Because she wasn’t attending school, she didn’t have a dorm room, which forced her to move off campus and put her belongings in storage.

She was left without a stable place to live and became homeless as a teen.

Heather’s experience being unhoused was emotionally difficult. While she was sleeping one night in a park, she said a man with a gun approached her and threatened to shoot if she made a sound. He proceeded to sexually assault her. When reported to the police, she said authorities didn’t seem to work hard to find the man.

“I was treated as a druggie runaway, not worthy of much time nor investigation,” she said in a blog post from 2017.

She was living on the streets for nearly five months until she found an available space in the basement of a woman’s house. But after about seven months, she came home to a note on the basement door informing her they were being evicted. With only 24 hours notice, she became homeless once again.

Although some details of being unhoused are hazy, Heather said she remembers how it felt clearly.

“I got judged a lot,” she said. “I got treated like I wasn’t important.”

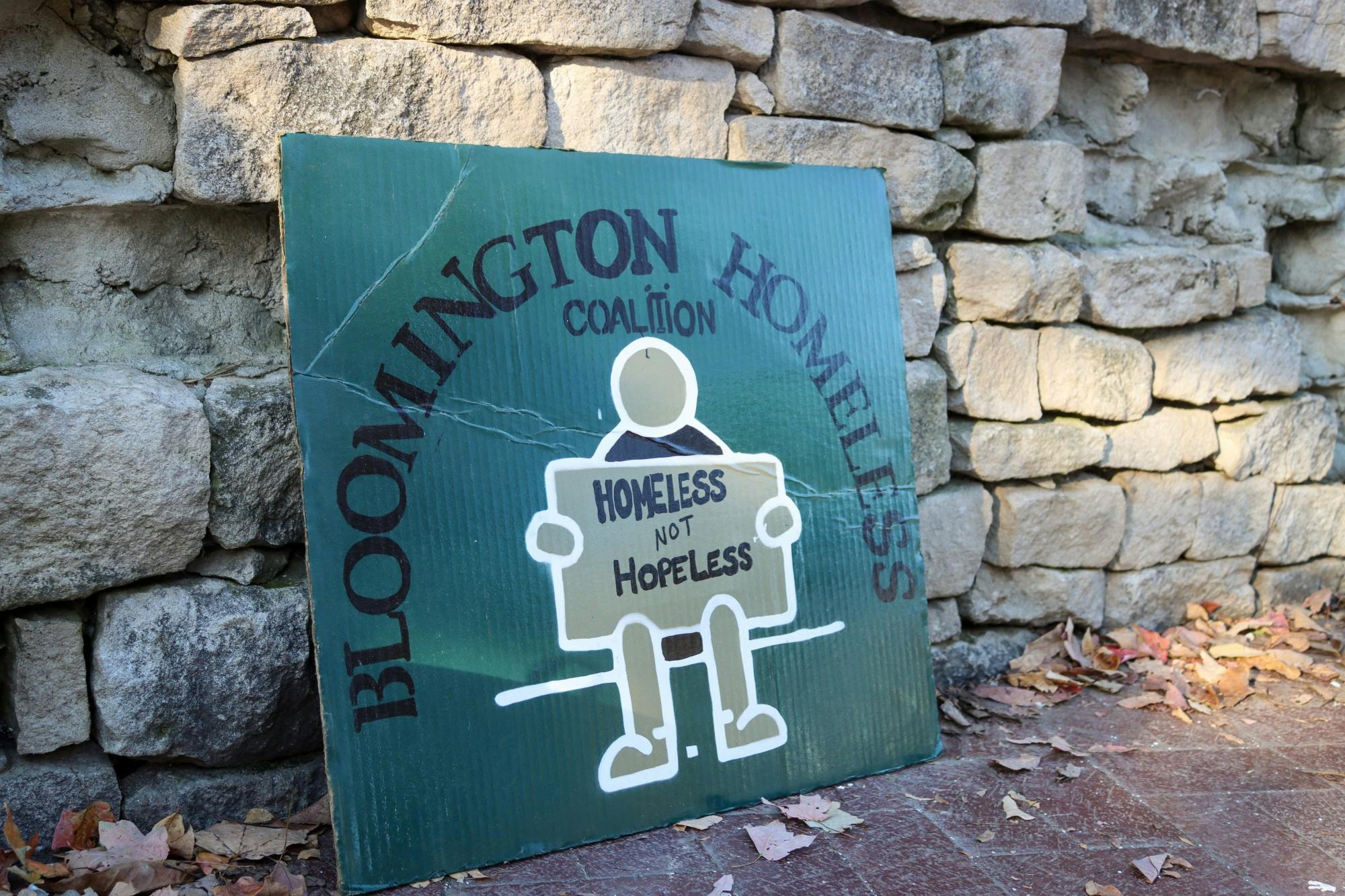

Eventually, she found a one-bedroom apartment she shared with a few friends and later met a woman at a music festival who she became close friends with. She invited Heather to move to Indiana, so the two of them moved to Evansville for a short time before coming to Bloomington, where she began doing advocacy work in 2000. She ended up becoming a part of the Bloomington Homeless Coalition, where she now spends her time volunteering and is the president of the board.

Heather said there are times when the only reason she hasn’t been homeless is because others have helped her while she was at her lowest.

After a car accident that left her with a traumatic brain injury at 17, she didn’t have a support system nearby, but a German family that witnessed the crash took care of her during the week she spent recovering in the hospital. Heather doesn't remember much from the accident, but she remembers their kindness fondly. There are others that provided support too: her aunt took her in for a couple of years when she was 23, and she stayed with a friend while waiting to get Section 8 housing.

She now lives in Section 8 affordable housing, with a roof over her head and enough food to eat. She doesn't have family in Indiana, but she has many friends, like fellow volunteers at the BHC.

In 2017, she worked as a Starbucks barista for a year and a half, but after encountering issues with memory loss and concentration, it made traditional jobs hard to keep. But volunteer work is more flexible since she can take off days if she needs them. She said she feels advocacy work is her purpose.

“All this work benefits me incredibly,” she said. “This is my job. It’s my reason to get up in the morning.”

With more stability in her life, Heather said her goal is to give people experiencing homelessness a safe space to relax.

She said she enjoys coffee hour because it’s a way to give back to those in need as someone who knows firsthand the struggle of being unhoused. She wishes there had been a program like this when she was on the streets of Kansas City.

“I hope they feel like the world is a little friendlier of a place,” she said. “That people care about them, and not everyone wants them to just move along.”

The City of Bloomington isn’t doing enough to help those experiencing homelessness, Heather said. She said she wishes the city would allocate a space for the unhoused community to safely and legally live. For now, she is working with the BHC and other organizations to provide those resources.

Heather said the city should focus on creating affordable housing options for people with limited income.

Temporary shelters can provide refuge, but not every shelter is ideal for every person. A few organizations in Bloomington have shelters, Heather said, but some people would still rather spend their nights outdoors. She said this is because some shelters have rules that feel alienating to people experiencing homelessness, such as not allowing couples to sleep together at night, enforcing early bedtimes or being founded upon religious beliefs that not everyone holds. Last winter, Beacon Inc., an organization that aids people living in poverty and experiencing homelessness, set up a winter isolation shelter that the BHC helped run. In the shelter, Heather said they try to eliminate as many of these concerns as possible.

This past winter, in near-freezing weather, she often logged onto Bloomington City Council Zoom meetings and took her phone to the park to let her friends speak firsthand about the issues they experience. Heather said there would sometimes be up to 150 unhoused people, BHC members and other advocates speaking.

Hours before the Seminary Park eviction on Jan. 14, 2021, nearly 100 people—including dozens of Bloomington residents—joined a City Council Public Safety Committee meeting to voice their anger and concerns about the plan to remove people from the park.

“These people are my friends,” Heather said during the meeting. “I know things about them. I don’t know what’s going to happen to them. I don’t know where they’re going to go.”

Later that night, Bloomington Police Department officers began removing items from the park. Heather was there that night, helping people gather their belongings and finding places to go. She said she watched as police evicted people experiencing homelessness from one of the only places they had to stay.

Earlier in the pandemic, Bloomington paused an ordinance that requires anyone setting up tents in a public space between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m. to have a permit. But as of December 2020, the rule was implemented again.

Heather said they’d been previously told an eviction would take place, but she doesn’t think people at the park were given enough time to move elsewhere, forcing some to leave their belongings to be thrown out or ruined by the weather.

“I was angry with the city and the way they handled things,” she said. “I didn’t understand where else they were supposed to go.”

During the eviction, she felt particularly anxious about her close friend Aries, who had lived at Seminary. Aries had a tent set up at the park, and Heather said she worried about where he would go, if he would be arrested or if his things would be thrown into a garbage truck.

That night, she sat on the curb and cried.

Outside of Seminary Park, Bloomington and the United States at large face a complex homelessness crisis. With an estimated 5,625 people experiencing homelessness in Indiana on any given day, local organizations work to provide shelter, food and medical care. But multiple previous evictions, hostility toward the unhoused community and few places for those experiencing homelessness to stay mean the effort to make change is constant.

Much of the reason more isn’t done to help the unhoused community is because of classism and stigma leading some to label unhoused people as lazy or criminals, Heather said. People often treat the people in the park harshly. One day, for example, a man in a brown truck stuck his head out the window as he drove by Seminary Park yelling, “Get a job!”

“They have to deal with a lot of people hating on them,” she said.

Bryan, a Bloomington man who experiences homelessness and frequents the park, said there are stereotypes about unhoused people within society that aren’t always accurate.

“People think homeless people are thieves, think they’re dangerous, think they’re criminals,” he said. “That’s not necessarily true.”

There are people who think simple solutions to homelessness exist, but Heather said simply finding a job requires more support.

“Most of them don’t have a place to take a shower and clean their clothes,” she said. “They don’t have a mailing address or a phone. You have to have a lot of stuff in place first, really, to go and get a job and keep a job.”

Mental illness is also an obstacle preventing some people from working. In a 2020 report from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 580,466 people were reported to be experiencing homelessness on a single night in the U.S. on average According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 20.5% of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. have a serious mental illness. In some cases, this can lead to cognitive and behavioral problems that make it difficult to carry out daily activities or earn a stable income.

Still, poverty and a lack of low-income housing are the primary factors preventing individuals from finding secure living situations, according to the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation.

Although something as small as coffee might seem insignificant, BHC board member Marc Teller said it’s a vehicle through which larger change is created.

“Caffeine and hot drinks—that’s the small things,” Marc said. “The coffee is a side effect. The attitude and the changing of minds is paramount to what the BHC does.”

Marc described Heather as a “mascot of open heartedness and open mindedness.” When she started volunteering, he said, she went to areas in Bloomington that some people—even other organizations—consider to be more risky. But he said Heather made a point to show that everyone in need, no matter where they are, is worthy of help.

“All of a sudden people started not only knowing her, but respecting her and knowing that she never meant ill will towards them,” Marc said. “She never judged them.”

Joe B. Little is a Bloomington man who experiences homelessness. He said people like Heather who help those in the park create a community and can save lives. When people are focused on simply staying alive, he said their brains and bodies don’t get the nutrition they require.

“Sometimes through the day, people might be dehydrated or they need nutrients and stuff, trying to survive,” Joe said. “Refreshments in the morning—coffee, stuff like that, and water — it’ll really help save a life.”

Last winter, the Beacon winter isolation shelter gave people a chance to find refuge from the cold in a place that wasn’t as cramped as some of the other shelters in town.

One night as people were waiting for the shelter to open at 9 p.m., Heather said that snow had collected on top of their blankets. To keep people warm, she placed the coffee underneath their blankets so they wouldn’t have to move. She also brought hand warmers, gloves, coats and scarves.

If it was seriously cold, she said, she wasn’t going to just sit in her car. She had to help.

In December 2020, a 51-year-old man known as “JT” was found dead in Seminary Park on Dec. 24. Several people previously told the IDS they believed he froze to death. JT’s death was one of two within the unhoused community in the span of two days.

Heather said she and other BHC members were shaken by the incident.

“I feel like we did a good job last winter,” she said, “Unfortunately, there’s always people that fall through the cracks.”

Although the work Heather does is crucial, it can weigh on her sometimes.

“I’m not always the best at taking care of myself,” she said. “I tend to go and go and then I crash and burn.”

There’s a lot of things that keep her up at night. She said the world is a scary place, and it can be easy to feel powerless in the face of overarching issues such as homelessness. She’s hopeful the BHC will be able to help more people this winter, and that the city will eventually step up to improve living conditions.

Even though the inability to help everyone can leave her feeling guilty, it also encourages her to work harder.

With each cup of coffee, each conversation with a friend, each Saturday morning spent at the park, she’s able to feel like she’s putting a drop of goodness into an ocean of hardship. And that, she says, makes her happy.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated which organization started the winter isolation shelter.