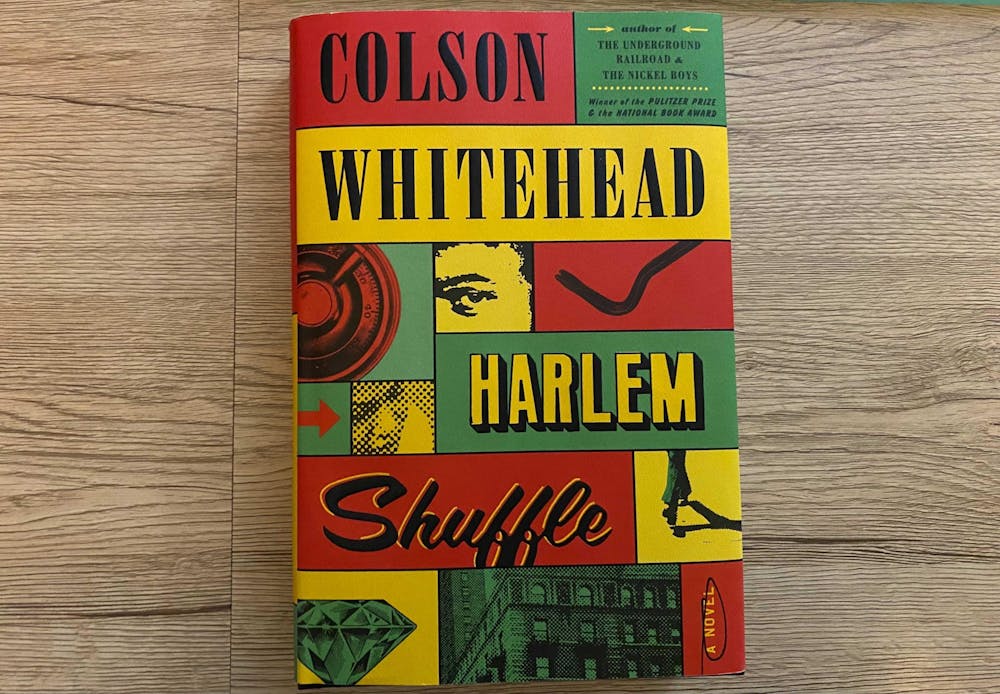

People always say not to judge a book by its cover, but I’ll be frank: I plucked Colson Whitehead’s “Harlem Shuffle” off its shelf because I figured if I was struck by the cover’s partial sketches, red, green and yellow blocks and a mixture of fonts, chances were high I’d be struck by the story enclosed inside.

And I was.

Whitehead’s latest book is an ode to “the biggest nobody in Harlem.” The three-sectioned story follows furniture store owner Ray Carney, a mostly devoted family man and sometimes-reluctant criminal across the better half of a decade.

COLUMN: Amor Towles’ ‘The Lincoln Highway’ meets high expectations

Carney is the son of a man known for breaking kneecaps and serving periodic stints in jail, but he slides into the world of illegal activity mainly by accident. We meet Carney in 1959, the year he adds criminal middle man to his resume, thanks to his cousin Freddie name-dropping Carney to a crew he’s not sure totally trusts him to be in on its next heist.

Carney becomes a fence — receiving stolen goods and reselling them at a profit — and little else goes according to plan.

“Harlem Shuffle” is a sort of introspection into the duality of man, or at least the duality of Carney.

He describes himself as not crooked, but bent. Whitehead plays with traditional character development, steering Carney down a path that is not quite straight and not quite narrow. The product of his character development shows the reader not just Carney’s growth, per se, but rather his increasing ability to be honest with himself.

Whitehead sums this up accordingly: “He’d spent so much time trying to keep one-half of himself separate from the other half, and now they were set to collide. But then — they already shared an office, didn’t they? He’d been running a con on himself.”

A Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winner, it’s not surprising Whitehead tells American stories well.

This work dives into the past, touching on the Harlem riot of 1964 following the murder of 15-year-old James Powell by police. The racial injustice reflected in the third installment of the novel serves as an eerie and disheartening parallel to today’s.

Whitehead gives readers flawed characters that grapple with one’s perception of “right” and “wrong,” a marker of successful fiction.

Peripheral and main characters alike are named and fleshed out. We’re greeted, for example, by Chet the Vet, an enforcer who went to veterinary school for one month before succumbing to other ventures; Pepper, an oddly likeable, loyal safecracker who we see kill more than one character; and Chink Montague, a gangster who was staying at the hotel that was the setting of the book’s original heist.

More: COLUMN: Why adults should read children’s book, ‘Beautifully Me’

Whitehead’s grasp of language allows him to juggle dry humor and ice-cold straight talk, regardless of subject matter.

He swings from a dialogue exchange in which the crime-adjacent, furniture salesman Carney says he’d like to bring Pepper in on a job, to which Pepper responds: “What, you need to move a couch?” to a stinging observation of the 1960s (or 2020s) reality, asking, “What had started it, the mess this week? A white cop shot an unarmed Black boy three times and killed him. Good old American know-how on display: We do marvels, we do injustice, and our hands were always busy.”

Whitehead doesn’t use his eloquence to hide from tricky topics, and the book effectively challenges readers to reevaluate their conceptualizations of inevitability and choice. He uses Carney’s indecision between criminal and clean to show that all people, all things can fall one way or the other, can go “good” or “bad” with the flip of a coin.

I added this book to my stack because of its zany cover: blocks stacked on top of one another, featuring the dial of a safe, an emerald, a corner storefront and more elements extracted from the book. The block that does the best job of encapsulating the story, though, doesn’t hold a sketch of a character or item. It’s a red block under the author’s name that looks like a paintbrush has been dragged across a page. Like Carney — like “Harlem Shuffle” — it’s not crooked, exactly, just bent.