I wrote an obituary about an IU law student, Purva, who was struck and killed by an SUV during my sophomore year on the IDS news desk. It was devastating. I spoke with the victim’s friends and family and learned as much as I could about who she was to tell her story.

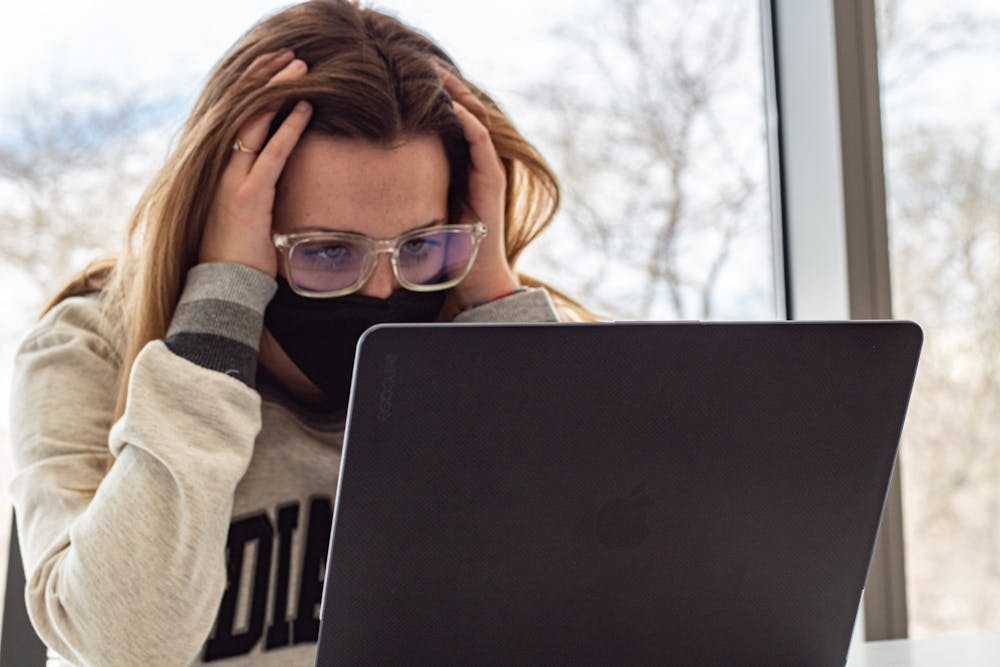

We never talk about mental health for journalists. Society sees us as these soulless beings programmed exclusively to receive information and regurgitate it into a digestible story for readers. It appears methodical and robotic. And how could it not?

Many depictions of journalists portray us as ambulance-chasing leeches, anxiously awaiting our big break — but that couldn’t be further from the truth.

The article about Purva took me weeks to finish. Deadlines are integral for journalists, but mustering the courage to write this story felt impossible. Though I finally produced something I hoped was an accurate and flattering recount of her life, it left me shaken.

The obituary stayed with me. Now, I almost never cross the street when other cars can turn into the crosswalk unless I’ve quadruple checked my surroundings and my friends don’t always understand when I grab their collar before they casually stroll across the road.

Sometimes, I think about where Purva might be as she was getting ready to graduate law school with a job before her tragic accident. I actually think about her all the time — and she’s someone I’ve never met.

And that’s the thing about journalists. We all have at least one story or source that for whatever reason completely sticks with us — one we’re unable to let go of. Quotes and faces often blur into my mind’s obscurity, but never those I spoke with for the obituary. Never those who knew Purva.

My job as a campus administration reporter was broad and covered various topics but for some journalists, these kinds of stories are their entire beat. Some only cover tragic events or people who’ve died. It wears on you after a while.

I’ve been in the newsroom. I’ve seen the hard work and dedication to the truth embodied by everyone who works there. I’ve seen reporters cry over stories and deadlines, working tirelessly to get things right. These behaviors often go unnoticed.

Instead, journalists are expected to “get over it” and “move on” after reporting stressful and traumatic phenomena. We’re expected to ignore the influx of ruthless hate comments from strangers on the internet. Though journalists are typically more resilient to emotional stressors, that doesn’t make us immune to a constant bombardment of negativity from multiple angles.

Because today’s news cycle is seemingly plagued by a perpetual dark cloud looming over daily developments, it can be easy to get caught up in the storm. But journalists must preserve their mental health, just as anybody else.

Some psychology and journalism experts recommend prioritizing self-care and compassion to avoid just “getting over it,” calming the body down, talking to trusted friends or colleagues, factoring in recovery time and even engaging in cathartic activities following a stressful event. Others recommend setting clear and concrete boundaries to avoid further emotional stress, particularly for those from marginalized communities.

It’s important to remember there’s a person behind the byline. Journalists are capable of the same emotional and physiological responses to trauma as others. Reporting is a tireless and often thankless job, but that’s not why we do it. The opportunity to shed light on important issues and communities in need is sacrosanct and serves a purpose much greater than ourselves. And we wouldn’t trade it for anything.

I feel so grateful I got to know Purva through those that loved her. Though we’ll never meet in person, she’s someone who will stay with me for the rest of my life.

Being a journalist provided the opportunity to tell her story, and it’s something I treasure.

Natalie Gabor (she/her) is a senior studying journalism with minors in business marketing and philosophy. She hopes to one day find a career that tops her brief stint as a Vans employee.