If you read fiction to escape from reality, Imbolo Mbue’s “How Beautiful We Were” is not for you. If you read fiction to better understand yourself, the world and your peers pushing their way through the suffering also known as the human condition, Mbue’s work should be high on your to-read list.

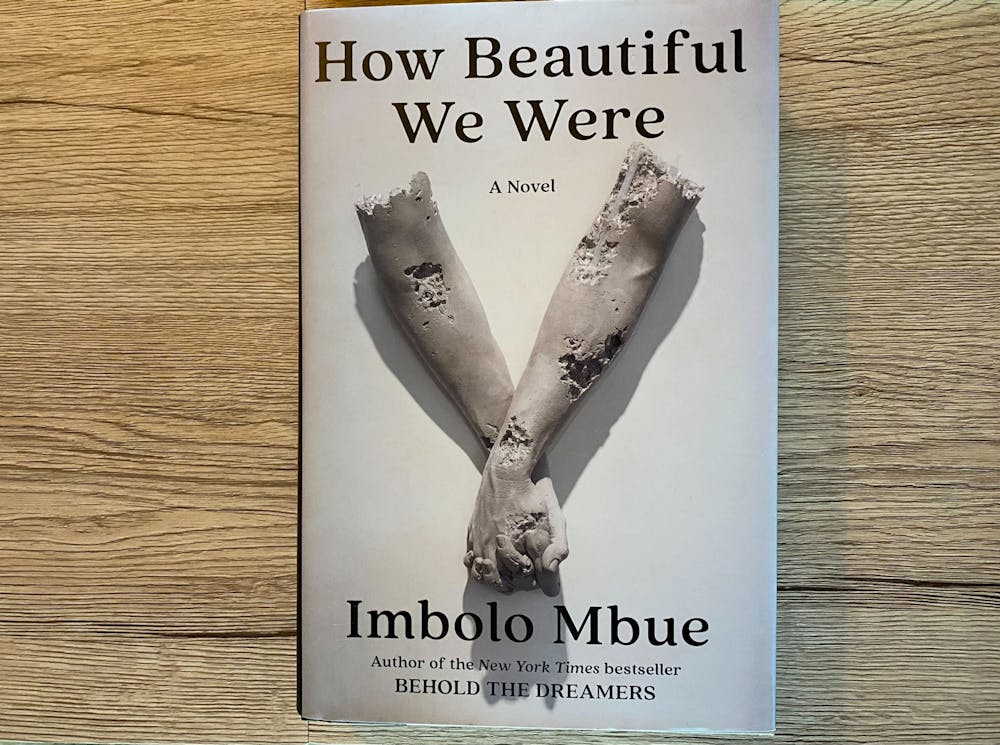

“How Beautiful We Were,” which topped the New York Times’ 10 Best Books of 2021 list last week, is the story of Kosawa, a fictional African village whose inhabitants are living through lethal environmental destruction heralded in by an American oil company.

When I read the book’s first paragraph, I knew the story would be a devastating one. It’s classified as fiction, but you could convince me it was longform reporting all too easily. It offers a look into our potential future the longer we go without properly addressing climate change and the longer we go prioritizing goods over people.

“We should have known the end was near. How could we not have known?” Mbue writes. “When the sky began to pour acid and rivers began to turn green, we should have known our land would soon be dead. Then again, how could we have known when they didn't want us to know? When we began to wobble and stagger, tumbling and snapping like feeble little branches, they told us it would soon be over, that we would all be well in no time. They asked us to come to village meetings, to talk about it. They told us we had to trust them.”

The story starts with catastrophe — children are dying from the polluted water sources, thanks to oil company Pexton. After lines of funeral processions carrying tiny caskets, things can’t possibly get worse, the townspeople think.

But rock bottom always has a basement, so naturally, things do, in fact, get worse. Fathers disappear, children keep dying, and uncles are sentenced to capital punishment under the country’s dictatorship. Just when you think education and activism might save the community after decades of international litigation, fires and emotional upheaval, readers are greeted with five more deaths and a whole lot of mistakes.

“How Beautiful We Were” is not altogether encouraging on the first read. It shows the fragility of people and our planet and captures the unspeakable despair marginalized communities face in a world where corporations and corruption reign supreme.

“‘Is the government a rock, a thing with neither brain nor heart?’ Papa yells as he turns to face Bongo. ‘Is the government not humans like us — people who have children, mothers and fathers who know what it’s like to have a sick child?’” Mbue scripts.

The government in this case is the one that sold Kosawa’s land to Pexton for its oil. Mbue comments on colonialism throughout the tale, which spans decades and is told through the viewpoint of a range of characters, young and old.

Mbue stitches the life of presumed hero Thula throughout alternating narration between The Children — a group of ever-dwindling numbers, Thula’s family and assorted community members.

In their stories, readers see parallels to exploitation around the world.

The pages echo Shell’s presence in the Niger Delta — which has been linked to environmental degradation, shortened life spans and destroyed ecosystems. Oil and natural gas extraction in Azerbaijan has subjected communities near extraction sites to poor air quality, failing kidneys and water full of debris, according to a 2018 human rights report.

Lest we look too far, we can see the effects of governmental mismanagement and misaligned priorities on the U.S.’ people as well, with the water crisis and environmental racism imperiling places like Flint, Michigan.

The list of people marginalized by our global focus on efficiency and profit goes on and on — both in Mbue’s fiction and in our reality. To me, the mark of successful fiction is its ability to provoke thought and emotion from readers.

Mbue inarguably meets this mark.