The night of April 5, 2021, Peter Jeske decided not to watch the NCAA Men’s Basketball Championship Game — the Gonzaga University Bulldogs versus the Baylor University Bears.

Peter was a lifelong basketball fan. He played throughout high school and later continued to play with friends at IU.

To watch the game, Peter’s roommate and friends gathered at a friend's apartment. His roommate asked if he wanted to go. He said no. Exams were coming up, so he decided to stay in and study.

Later in the day on April 6, his roommate found him dead. A small amount of fentanyl killed him.

Peter’s parents believe he took a counterfeit pill that he thought was a prescription medication like Xanax or a study drug like Adderall after a long night of studying.

“If he had been a little less concerned about studying for his classes and just gone with his buddies, he’d still be alive,” his father, Dean Jeske, said.

Peter’s decision to take one pill — a decision many college students make — ended his life.

A 2018 study from the Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education found that up to 20% of college students take prescription stimulants that are not prescribed to them for recreational or academic purposes. Another study from a peer-reviewed journal found that more than 40% of young adults in college reported misusing a prescription psychotherapeutic drug at least once in their lifetime.

But college students don’t take pills thinking they will overdose on fentanyl. This year, there has been a rise in counterfeit pills laced with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. In fact, the rise has been so severe that the DEA issued a Public Safety Alert in September for the first time in six years.

The Public Safety Alert warned that counterfeit pills were being marked as legitimate prescription pills and were killing users at an unprecedented rate. In 2020, over 93,000 people died from a drug overdose, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Counterfeit pills are made to look like real prescription medications such as Xanax, Vicodin or Adderall. The pills are widely accessible and often sold on social media. A significant number of high school and college students buy them, according to the DEA.

Dean thinks the conversation about counterfeit pills gets lost in the wider context of the opioid epidemic. He thinks addiction is a huge issue that needs to be addressed, but it’s separate from the issue of counterfeit pills — his son and others who died after taking a counterfeit pill didn’t have a substance use disorder.

University administrations across the country have sought to raise awareness of the widespread issue of counterfeit pills. A page on Colorado Boulder’s website reads, “Drugs laced with fentanyl in Boulder: Tips to stay safe.” On Stanford University's website, a 2020 letter from a university administration is titled, “Dangerous counterfeit drugs in our community.”

Public health officials across the United States, including those in Oregon, Maryland and South Carolina, have warned their communities, too.

Michael Gannon, the DEA assistant special agent in charge of operations in Central and Southern Indiana, said there is no way to tell whether a pill is counterfeit without a fentanyl test kit.

A potentially lethal dose of fentanyl is 2 milligrams, Gannon said — small enough to fit on the tip of a pencil. Fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine, he said.

Jon Agley, deputy director of Prevention Insights at IU, said there is a misconception that all fentanyl is bad or illicit, but fentanyl has legitimate medical uses. When correctly prescribed by a medical professional, fentanyl can treat severe or chronic pain, especially for those who have a tolerance to other opioids. Agley thinks misconceptions about fentanyl result from the selling and use of illicit fentanyl, which has become a driver of the overdose epidemic in the U.S.

Part of the problem with counterfeit pills is that they aren’t labeled correctly since they are made illegally and without regulation of their content, Agley said. Someone who thinks they’re getting Xanax or Adderall might be unknowingly taking fentanyl.

If someone has little to no tolerance for opioids, the risk of overdosing on fentanyl increases.

There is a spectrum of drug use, Agley said. A dependency refers to a physical dependence on a substance whereas addiction refers to a psychological or psychiatric dependence. Someone who uses a drug is not necessarily dependent or addicted.

There’s also an old misconception that only those with substance use disorders can overdose, Agley said, but that’s not true.

“That can happen to someone who's been using for years, or it can happen to someone the first time they use,” he said.

In Monroe County in 2019, there were 21 accidental overdose deaths related to fentanyl, Monroe County Coroner Joani Stalcup said. By 2020, this number more than doubled to 45 deaths.

In the past two years, Stalcup said she’s seen an alarming increase in the number of accidental overdose deaths. Fentanyl has been at the forefront of all of it, she said.

Naloxone, also known as Narcan, can reverse the effects of opioids, preventing overdose. Local pharmacies that offer naloxone can be found on the Indiana State Department of Health’s website. The Monroe County Health Department provides a naloxone nasal spray free of cost with a brief training on how to use it. For more information, call (812) 349-2722.

In 2019, the DEA seized 2.6 million counterfeit pills nationwide. In 2020, they seized 6.8 million. So far, in 2021, they’ve seized more than 9.5 million pills. Two of every five pills seized had a potentially fatal dose of fentanyl, Gannon said.

Though Gannon didn’t have an exact number of pills seized in his jurisdiction, he said the number was in the hundreds of thousands.

“It's worse than Russian roulette — every time you take a pill you're risking your life,” Gannon said.

This phrasing has been used often by the DEA for its “One Pill Can Kill” campaign. On the Today Show, DEA Administrator Anne Milgram said, “It’s Russian roulette, but it’s even more dangerous in one sense. In Russian roulette, people know that they’re passing around a loaded gun.”

When Dean first wrote about his son’s death on a LinkedIn post, he compared college students taking pills that weren’t prescribed to them to playing Russian roulette, like the DEA. But, the phrase from the DEA struck him. “It’s worse than Russian roulette.” Few people knew about the issue of counterfeit pills, he thought, and young people especially don’t realize taking one pill could kill them.

“I'm not trying to preach to young people about the dangers of drugs and alcohol or anything like that,” Dean said. “I just want them to be aware of this incredible risk that they're taking in this very, very focused area.”

Some young adults think using prescription drugs is safer than harder drugs like heroin, but counterfeit pills make them incredibly dangerous as well.

What looks like a Xanax could be a Xanax, but it could also be a pill laced with fentanyl.

Peter made a mistake, Dean said. A lot of people who take counterfeit pills have made that mistake. It shouldn’t cost them their lives, he said.

“It does,” he said. “It can, and it did.”

April 6, 2021, was the worst day of Dean Jeske’s life. That day, he answered a knock from his home in Illinois. There was an Illinois State trooper on the other side of the door. The trooper asked him if he had a daughter attending IU.

“No, but I have a son who attends Indiana University,” Dean said.

“Hold on a minute,” Dean remembers the trooper said, then walked back to his car.

Standing alone in his doorway, the same doorway his son had walked through just the weekend before, Dean began to feel sick to his stomach. He began to worry something very bad had happened to Peter.

The trooper’s next words were something no parents ever wants to hear.

Peter had died in his apartment.

Dean was overwhelmed by a wave of emotion. All at once, he felt multiple stages of grief jumbled together. Anger. Devastation.

Denial took hold. He couldn’t believe it. How could his son, a beautiful, healthy 22 year old be gone, just like that?

Quickly, his mind shifted to the realization that he had to call his wife, who was at dinner with her friends. He had no idea how to break the news to her. One moment life is normal, and then there’s a knock on the door and everything falls apart. How could this be real, he thought? How could this be real?

“That was the worst day of my life,” Dean said. “The next 24, 48 hours, two weeks, six months were the worst of my life.”

Before Peter’s death, Dean had never heard about counterfeit pills. Neither Peter’s family nor friends think Peter took pills often. Growing up, Peter had never had issues with substance use.

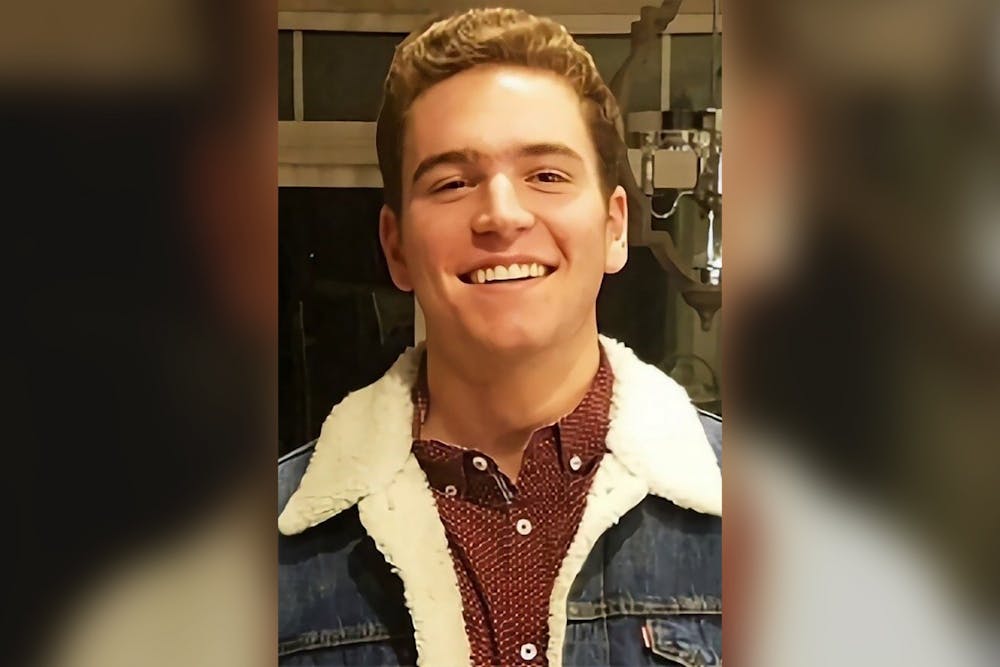

Peter Jeske was a happy, caring, well-adjusted IU student. He loved sports, was in the Acacia Fraternity and studied finance in the Kelley School of Business. It was his last semester of school at IU, and he had secured a job in Denver after graduation.

Peter was an outside-the-box thinker, Dean said. Of his three sons, Dean said he always picked Peter as the one to start his own business. He would routinely bounce ideas off of his father. Sometimes they were good ideas, a lot of the times they weren’t, Dean said while chuckling. Once, Peter pitched a business to his dad.

“That’s called Amazon,” Dean said.

“Oh yeah, I guess they do that already, don’t they,” Dean remembers Peter responding.

Peter’s smile would light up the room, his father said. He had a clever, quirky sense of humor. He was happily surrounded by friends and brothers at IU, but he was also careful about making sure everyone felt included.

After Peter’s death, one of his high school friends told Dean a story about a time he was hanging out with one of Peter’s friend groups for the first time. The friend was nervous, he said, because he didn’t know everyone. When he walked down into the basement, Peter ran over and gave him a hug. The friend told Dean he would remember that moment for the rest of his life because he felt welcomed.

At Peter’s funeral, Dean read a quote from Maya Angelou.

“I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Peter made sure no one ever felt left out. And even though he’s gone, his family and friends will never forget how he made them feel.