My favorite part about opening a new book is the dedication page. Some people skip straight to the first chapter, but I’m always curious about what words the author found most important, the ones that precede the story itself.

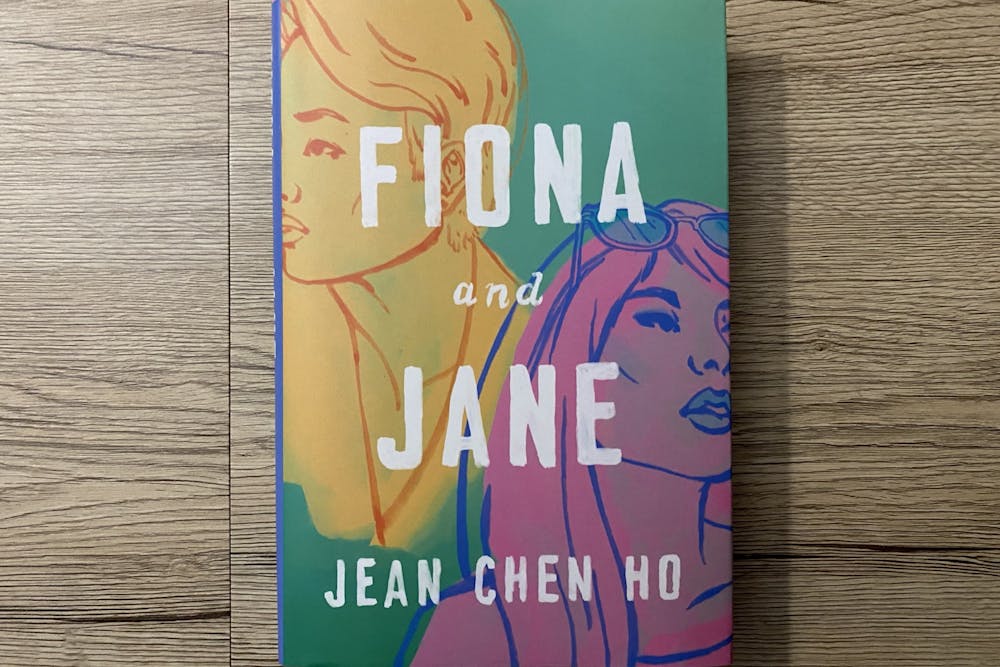

Jean Chen Ho’s debut “Fiona and Jane” opens by borrowing from novelist James Baldwin.

“I have always felt that a human being could only be saved by another human being,” the page reads. “I am aware that we do not save each other very often. But I am also aware that we save each other some of the time.”

“Fiona and Jane” is a story about that which Baldwin labels “some of the time.”

It is told from the alternating perspectives of two Taiwanese-American women across chapters and years. The chapters, which rotate between Fiona’s viewpoint and Jane’s voice, offer never-whole pieces of a friendship spanning decades.

Readers hear firsthand about Jane’s father, who is in love with his college friend Lee, about her first kiss with her piano teacher over Chopin’s Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor, about her too-short bob haircut courtesy of childhood friend Won. We’re privy to Fiona’s move to New York after graduation from the University of California, Berkeley, about her steps into and out of relationships with men, apartments and friends, about her ballet recital back when she was called Ona, an elementary school child in Taipei.

Related: [COLUMN: Colson Whitehead deserves a third Pulitzer Prize for ‘Harlem Shuffle’]

The book is soothing, but real. Its concrete details and honest prose lend a palpable sense of authenticity to “Fiona and Jane.”

As the friends glide in and out of each other’s lives, Ho paints relationships the way we actually experience them — rough around the edges, not painted in idealized, fictionalized sepia tones.

Experiencing more than 20 years of Fiona and Jane’s respective and collective lives in fewer than 300 pages allows readers to glean their life lessons without having to wait the full 20 years.

Through her storytelling, Ho reflects on both the universal and particular realities of growing up. Fiona and Jane grapple with difficult relationships in different capacities, with their parents, with their romantic partners, with each other and with themselves.

She gives words to experiences and feelings that before were unable to be contained by language.

Fiona becomes a mother, and Jane is happy for her — “But what was this other feeling buried within it?” Jane asks herself in a late chapter. “(Jane) moved through the apartment, from room to room, turning on the lamps, as though searching for something. Nothing was missing. She felt as lonely as she’d ever been.”

Ho highlights the capricious and often contradictory feelings mandated by young adulthood.

“To lose—and lose big—was a new and thrilling kind of freedom, when Fiona loosened her grip on shame,” Ho scripts, dissecting the nature of young adults through Fiona’s introspection.

This collection is fictional, but it doesn’t read like it. The characters, what they feel and how they act, are real. They’re authentic.

I now feel as though I know these characters intimately. My friends, Fiona and Jane. Jane and Fiona.