Editor’s Note: This story mentions multiple depictions of sexual abuse and assault. For anyone wishing to report a sexual assault or find help, a list of resources is provided at the end of the article.

Chris Parker was only a freshman, but he was already making a name for himself as a star drummer in the jazz studies program of the Jacobs School of Music. That winter, another IU student accused Parker of sexually assaulting her.

Shailey Ostlund, also a freshman, told investigators that Parker sexually assaulted her on Halloween in 2015 in a residence hall parking lot. She said Parker invited her to his Jeep and then leaned over the console and began touching her. When she tried to escape, she said she discovered that Parker had locked the doors.

Parker denied the allegation, but Ostlund filed a complaint to the university. After a six-month investigation, IU found the drummer responsible and suspended him for about 13 months.

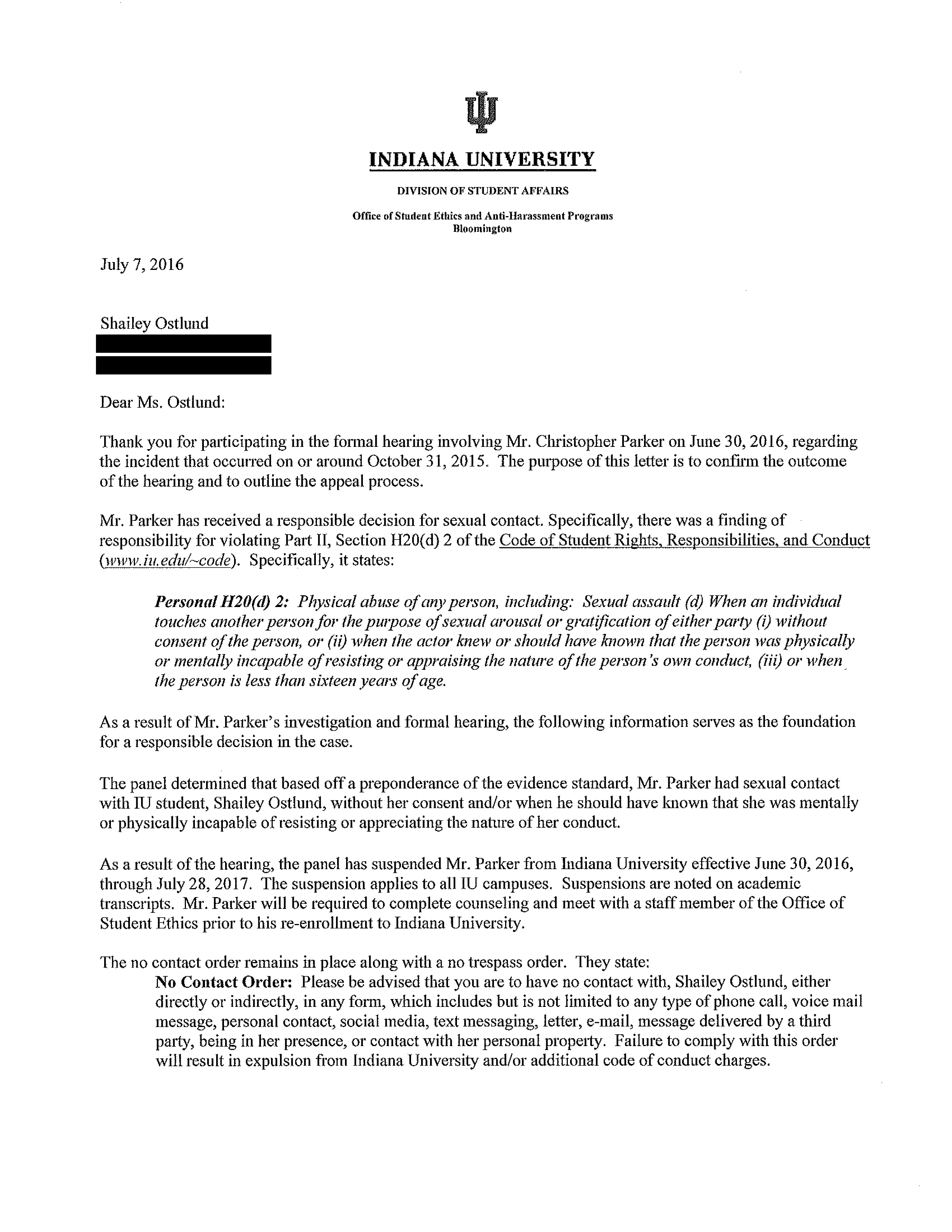

A letter sent to Ostlund with the outcome of the hearing and suspension information reads:

“The panel determined that based off a preponderance of the evidence standard, Mr. Parker had sexual contact with IU student, Shailey Ostlund, without her consent and/or when he should have known that she was mentally or physically incapable of resisting or appreciating the nature of her conduct.”

According to the terms of the suspension, Parker was forbidden from setting foot on campus. If he violated the no trespass order, IU told him he would be expelled or charged by police, or both. But when Parker broke those terms, returning to campus to record at a radio station, the university did not follow through. He wasn’t expelled, and the IU Police Department confirms that no violation was reported. Instead, IU simply suspended Parker again.

Why did the university cut Parker a break? IU officials won’t comment on any student’s conduct record in alignment with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

***

What happened to Ostlund that night evolved to be much larger than herself and Parker. The university’s and Jacobs’ response, or lack thereof, to the Ostlund’s case and Parker’s consequences has caused a ripple effect within the community of current students and alumni of the jazz studies department.

In the over six years since Ostlund’s assault, Parker served two suspensions and returned to take classes at IU’s prestigious music school in 2020. He is currently finishing his undergraduate degree.

IU alumna Abby Malala is helping organize an open letter expressing disapproval in the university’s decision to allow Parker back as a student.

“They say in Jacobs, ‘if you can play, that's all we care about,’ especially in the jazz scene,” Malala said. “They apply that logic to people like Chris Parker.”

She was motivated to do so after she saw Parker performing at a local music festival, called Realfest, on July 17, 2021, in Dunn Meadow. The festival organizers apologized to the community for his inclusion soon after.

Multiple jazz faculty members played with Parker in off-campus gigs and on his album during his first suspension spanning June 2016 to July 2017. They continue to play with Parker in gigs. However, the university did not communicate much information to jazz faculty regarding Parker’s disciplinary record or allegations, which IU says is due to FERPA protections. Jacobs faculty and staff said this caused them to be largely in the dark.

Multiple current students, alumni and faculty said Parker is a great talent in the school based on his playing ability on the drums. Parker started attending IU and Jacobs in 2015 on a full-tuition scholarship, majoring in jazz studies, according to his website. Many alumni allege he wouldn’t have been given so many breaks had he not been so talented.

“For somebody that talented, what is our right to squish that career?” IU professor Monika Herzig said. “He's been a victim of a bunch of weird circumstances.”

Students have said they feel unheard. In a 2017 petition when Parker returned to school for the first time, female students said their feeling of safety in the department was jeopardized. Parker was suspended soon after due to a violation of his original suspension.

Looking back, Ostlund and other alleged victims of sexual abuse believe the system failed them.

Parker did not respond when the Indiana Daily Student reached out to him nine times for comment or an interview.

As of the night of Jan. 26, Parker deactivated his Facebook and Instagram as well as his website. This was done prior to this article publishing.

Ostlund started attending IU as a freshman during the fall semester of 2015. She grew up in Bloomington, attended Bloomington High School North and had a good number of friends, including Parker, in the area.

On Halloween, Ostlund, Parker and their friends were partying and drinking in a dorm room at Forest Quadrangle. Parker asked the group if anyone wanted to go down to his car to smoke with him. Ostlund, who said she was heavily intoxicated, was the only person to oblige.

Walking down to the van, Ostlund fought with herself. She and Parker had a history — they had dated in high school for nine months, a relationship she described as unhealthy, toxic and abusive.

She had hung out with Parker a few times in college, afraid to say no to his invitations. She felt they could be just friends, but she was still nervous and didn’t fully trust him. She said he understood her, and she wanted him to care for her.

But she still followed him out to the van that night. She didn’t think he would do anything with her friends upstairs.

Advertisement

They climbed into his Jeep van in the residence hall parking lot and began talking. Ostlund confided in him about keeping up with her classes and struggling with her depression and anxiety. She just wanted someone to confide in, and he was a great listener.

Parker began leaning in over the center console. She told him to stop. She told him no.

Panic exploded in her head. Her only thought was that she needed to get out.

At that moment, she said she had realized he had locked the doors.

Parker molested her and attempted penetration with his hands and mouth, Ostlund said.

She fumbled around the center console of the van, searching for escape. She found the button to unlock the doors and stumbled out of the van toward the residence hall’s doors. She called her friend on the phone to let her in and pretended to still be on the line once they hung up.

“I was so overwhelmed with everything”

After Parker’s assault, Ostlund’s mental health rapidly declined. She said sometimes she couldn’t bring herself to even leave her father’s house in fear of seeing Parker.

OSTLUND: I was so overwhelmed with everything. I knew that I just needed to be in a place that was safe, which was my dad's house, because I didn't trust myself outside. And I couldn't handle it. I couldn't handle being in school and I couldn't handle seeing people. I especially couldn't handle the idea of seeing Chris.

“I was so overwhelmed with everything”

After Parker’s assault, Ostlund’s mental health rapidly declined. She said sometimes she couldn’t bring herself to even leave her father’s house in fear of seeing Parker.

OSTLUND: I was so overwhelmed with everything. I knew that I just needed to be in a place that was safe, which was my dad's house, because I didn't trust myself outside. And I couldn't handle it. I couldn't handle being in school and I couldn't handle seeing people. I especially couldn't handle the idea of seeing Chris.

It was about 3 a.m. She was alone and feared he would do something else.

Her friend let her back inside and they returned to the dorm room. Ostlund sat contemplating what had happened, the thoughts thrashing in her head. She recorded a video, which was used as evidence, of herself documenting what she said happened in the van.

“Shailey, you're recording this video just so that you remember that Chris assaulted you tonight,” Ostlund recalls saying in the video.

She thought she was too drunk. She thought she wouldn’t remember. She felt she needed to remind herself for the next day.

Today, she retains a few memories from that span of months and years after her case. But she hasn’t forgotten a detail of the assault.

She dropped out of IU less than a month later.

Ostlund’s mental health plummeted, and she was later diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. She was living in a constant state of fear. She had multiple panic attacks a week. She couldn’t hold a full-time job. Just hearing Parker’s name triggered her. She stopped leaving the safety of her dad’s house. Going out meant seeing people. Going out meant she may see him.

“I was really struggling to survive and to just be myself,” Ostlund said. “I was just really worried that I'm Shailey, I'm the person that Chris Parker assaulted.”

***

Ostlund opened a case against Parker to the then-named IU Office of Student Ethics and Anti-Harassment Programs in December 2015, with IU beginning to work on her case in January.

What Ostlund said happened to her falls into the university’s definition of forcible fondling, the touching of another person’s body for their own sexual gratification non-consensually. The university considers this act to be within its definition of sexual assault.

Since Ostlund had no physical evidence of the sexual assault, she didn’t go to the police. However, she said she was able to receive a restraining order through the Bloomington Police Department against Parker when the university’s protective order expired.

Police ask that sexual assaults be reported as soon as possible so police have a greater chance to gather the evidence needed to make an arrest, according to IU’s Stop Sexual Violence initiative. However, assaults can be reported without seeking prosecution and police can take steps, knowing of the report, to keep students safe.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do it without help”

Ostlund reported Parker's assault to the then-named IU Office of Student Ethics and Anti-Harassment Programs with the help of Matthew Waterman, Parker’s roommate and a high school friend of both Parker and Ostlund.

OSTLUND: I’ve always considered myself to be a feminst, since the moment I knew what the word “feminism” was. And I never thought that I would be the person who would be in a situation like this because I always thought I would be able to stand up for myself and say no. I always wanted to be the person who was able to report something like this but I wouldn’t have been able to do it without help.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do it without help”

Ostlund reported Parker's assault to the then-named IU Office of Student Ethics and Anti-Harassment Programs with the help of Matthew Waterman, Parker’s roommate and a high school friend of both Parker and Ostlund.

OSTLUND: I’ve always considered myself to be a feminst, since the moment I knew what the word “feminism” was. And I never thought that I would be the person who would be in a situation like this because I always thought I would be able to stand up for myself and say no. I always wanted to be the person who was able to report something like this but I wouldn’t have been able to do it without help.

Ostlund said the office told her at the beginning that the investigation and hearing process into her allegations would take a maximum of six weeks. Instead, she had to endure a six-month process. The extended time span forced Ostlund to continuously revisit her trauma. She said she retold her story over and over, trying to find a way to make university staff listen, believe and care.

“I was not in a place where I could be spending all of my time thinking about this,” Ostlund said. “And the amount of time that I had to spend thinking about it already was overwhelming.”

Kathy Adams Riester, associate vice provost for student affairs, said the amount of time each case takes changes due to the variability of factors, like how many witnesses there are and the amount of information that is available. She said the Office of Student Conduct investigators work to make the process as thorough and timely as possible. Libby Spotts, senior associate dean of student affairs and director and deputy of sexual misconduct & title IX coordinator, said the office attempts to give the person making a complaint a time period based on the number of witnesses and amount of information needed to be investigated.

Ostlund said working with the office for the investigation was like working with a brick wall because she had trouble submitting information. She said there were few helpful resources for her emotionally.

Advertisement

“I don't think that they appreciate how difficult it is to be on the other side of it,” Ostlund said. “I have worked really hard just to try to get IU to understand the gravity of the situation.”

Spotts said the investigators collect evidence through interviews, witnesses and given information. Investigators will reach out to those involved asking for their help in this collection, she said.

A major consideration during this process is the mental health of the person reporting, Spotts said. Investigators try to be as transparent as possible with those involved, she said, and interview people with their trauma in mind while collecting information. Confidential Victim Advocates is a resource for students who want extra updates and to talk through the process.

A preponderance of evidence in a student conduct case means the evidence provided to investigators shows that a violation of the Code of Conduct is more likely than not to have occurred, Adams Riester said in an email.

In June 2016, an IU hearing panel found Parker responsible of sexually assaulting Ostlund and suspended him for just over a year. Ostlund received a no contact order and a letter noting the consequences if Parker violated his suspension.

|

Suspension Letter Following a six-month long investigation, IU found Chris Parker responsible for sexually assaulting Shailey Ostlund in 2015. Parker was suspended for about 13 months, meaning he couldn’t step foot on campus. If he did, IU said he would be expelled or reported to the police, or both. Source Shailey Ostlund Scroll |

|

|

|---|

Before his suspension had expired, Parker was back on campus in spring 2017 to play at a local radio station, according to six sources. He returned to classes in fall 2017 but was promptly dropped from them. Ostlund assumed he had been expelled at this point since Parker did not have a criminal record. The terms of his suspension meant at least one of the two should have happened, according to the letter.

Ostlund then learned Parker was back taking classes at IU during the fall semester of 2020. When she questioned the Office of Institutional Equity about his return, she says they told her they decided to suspend him a second time instead of expelling him, and she could not appeal.

Ostlund said it is frustrating to have gone through what she described as an emotionally difficult reporting and hearing process just for the outcomes of that system to not be upheld. Still, she doesn’t regret going through that process.

She was glad Parker received a punishment, but she said she thinks now there should be a harsher consequences for sexual assault. To many, she said Parker’s suspensions and punishment can be considered a successful outcome of the system compared to the many cases without such a verdict.