“The world is falling to pieces and everything almost always goes to shit and we almost always hurt the people we love or they hurt us irreparably and there doesn’t seem to be a reason to harbor any kind of hope, but at least this story ends well, ends here, with the scene of those two Chilean poets who look each other in the eye and burst out laughing and don’t want to leave that bar for anything, so they order another round of beers.” — Alejandro Zambra

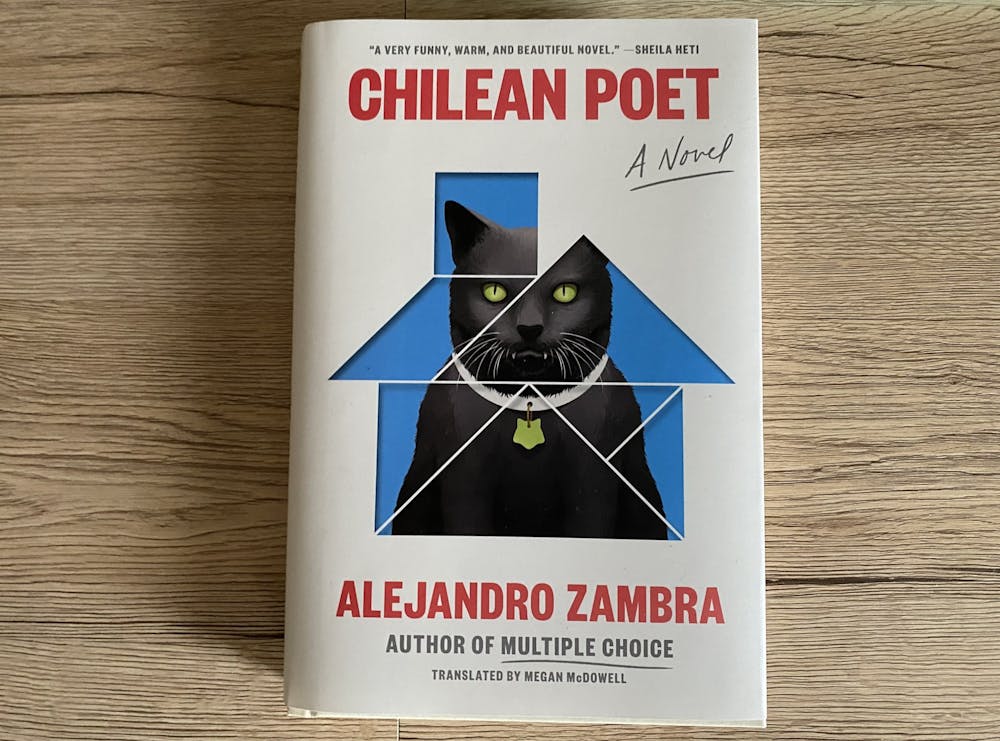

Published in Spanish in 2020 and in English earlier this month, Alejandro Zambra writes about identity in the much-awaited release “Chilean Poet.” Through the eyes of temporary stepfather Gonzalo Rojas, Zambra considers what it means to be a parent, especially when your language doesn’t have an effective word for your role.

Readers witness snapshots of Gonzalo’s life: The book begins in 1991 when Gonzalo is a teenage poet. He is dating a girl named Carla — who does not share his appreciation for poetry. Their adolescent relationship takes up the first section of the book, called “I. Early Works,” nodding to the book’s titular theme.

Gonzalo and Carla later break up, run into each other after about a decade, have what one party assumes is a one-night stand, and eventually become a family: two mismatched but enthusiastic partners raising Carla’s six-year-old son, Vicente.

One of the first impactful scenes of the book occurs when a grocery clerk asks about Gonzalo’s relationship to Vicente. He could be, Zambra supposes in this chapter, an indulgent uncle, an older brother or a live-in clown. He is, technically speaking, the boy’s “padrastro,” but Gonzalo is not content with the word.

In Spanish, the suffix -astro “forms nouns with pejorative meanings,” Zambra quotes from a Spanish dictionary. Gonzalo is frustrated with the lack of a proper word for his place in his stepson’s life.

What feels almost like a linguistic tangent on the first read develops into a major question of the novel: What role do the people with undetermined or insufficient titles play in our lives?

This question reverberates throughout the remainder of the novel, as Gonzalo’s presence turns into absence. After years raising Vicente, and losing a second child with Carla, he moves to New York to complete his doctorate. Carla asks him to stop talking to Vicente, and he listens.

What is the word for the son who was not your son but you raised as if he was? What do you say when you are asked if you have children, when you had a stepson and your partner experienced a miscarriage, but technically you don’t have kids waiting for you at home?

Readers only witness Gonzalo grapple with these questions in the periphery. The second half of the book orients us in now-18-year-old Vicente’s life. Vicente has, somewhat ironically, become a poet.

He meets an American journalist and pitches a story about common Chilean poetry — not Pablo Neruda, no Gabriela Mistral — to her. Through Zambra’s articulation of her reporting, readers are submerged into a Beat-Generation-adjacent world of every iteration of the common Chilean poet.

Zambra’s descriptions of this sub-culture in Chile act as an ode to poetry itself. He drops poems deemed good and bad on occasion in the 350-page-plus book, appreciating the craft in all its forms. His characters and plot “prove poetry is good for something, that words can wound, throb, cure, console, resonate, remain,” he writes.

These chapters will unequivocally make readers want to book a one-way flight to Valparíso. Gonzalo, too, decides to come home, and by chance runs into Vicente.

They reunite, once more becoming something like friends, something like family, something that doesn’t have a proper title. They are, at least, both in “the whole big little world of Chilean poetry,” as Zambra writes.