A man’s voice travels down the phone line and onto the radio from inside an Arizona prison. It’s Episode 287 of WFHB’s nationally syndicated Kite Line Radio.

Adrien Espinoza has been in and out of Arizona prisons since he was a teenager. He said he spent two years between juvenile detention centers for a misdemeanor that would have gotten an adult six months and a fine.

As a teenager, he said he was sent to the Adobe Mountain School, a juvenile detention center where the Justice Department found “disturbing” patterns of sexual and physical abuse by staff.

As a punishment, he and his peers sometimes wouldn’t be allowed to go to classes, he said. When he was released at 18, he had almost no high school credits. The very resources the state said were supposed to be rehabilitative became a privilege.

Now, decades later, he’s relaying his experiences to Kite Line’s nationwide audience from inside another Arizona prison.

“Arizona is just throwing us away because they don’t give a shit about some little brown kid who’s got no money,” Espinoza said on the show.

Espinoza can’t step beyond the prison walls, but Kite Line is making sure listeners have a chance to hear him far beyond them.

In 2016, incarcerated people began organizing a nationwide prison strike to begin on Sept. 9 of that year. The strike would consist mostly of work stoppages, but it also included hunger strikes and protest marches in prison yards, growing to more than 24,000 participants across a dozen states.

They were going to need people on the outside to know about it.

A handful of people who knew each other from doing prisoner support — writing to prisoners, helping with their cases, sending them books — knew about the strike in advance. They wanted to find a way to amplify and support the strike, to show that people on the outside cared. Mia Beach was one of them.

Her idea? Kite Line Radio, a weekly radio program covering the prison system.

“At the time, there weren’t a bunch of shows doing this,” Beach, the producer and host of Kite Line, said. “It felt really important to create a media outlet that is not very censored, that we’re able to just air what people need for us to air.”

With the support of the Bloomington community radio station WFHB, Kite Line’s first episode aired about a month before the strike began. This small team, bound together by their experience in radio, prisoner support or both, created a project that has aired every week since, totaling over five years and nearly 300 episodes.

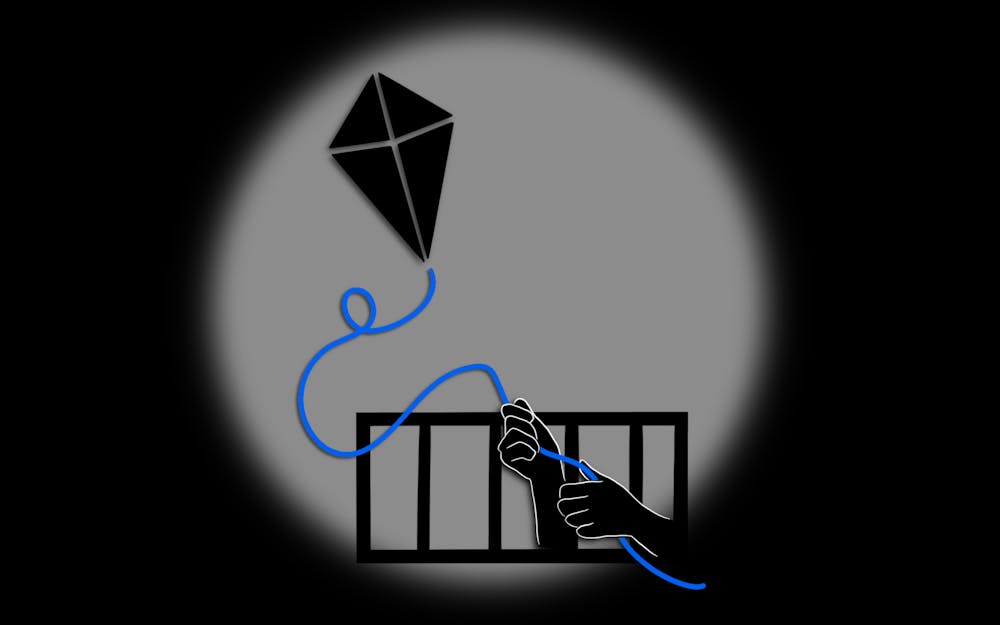

The show’s name refers to what a “kite” is inside of prisons: a message. Whether it’s passed from inmate to inmate or to a guard, on paper or by word of mouth, it requires trusting other people to pass it along to its destination. As Kite Line explains at the top of each episode, the show serves to pass messages to the outside world.

Radio lends itself to one of Kite Line’s main goals: to reach listeners who aren’t actively seeking out coverage of the prison system.

“Our hope is that someone is flipping through the radio dials on their way back from work, and maybe it’s not someone who’s sympathetic to someone who is affected by prison, or someone who’s in prison,” Beach said. “But maybe they hear this story before they realize that’s what they’re hearing.”

Kite Line’s archives show that life behind bars isn’t the same for everyone. Some episodes cover the basics — defining commissary, explaining how to write to prisoners — but many dive deep into specific lived experiences, like pregnancy and childbirth behind bars or solitary confinement. Others are dedicated to carceral history or theory.

Kite Line strives for more than education and empathy, though. Micol Seigel, a professor of American studies and history at IU who has volunteered at Kite Line from the beginning, stressed that Kite Line is not a “neutral knowledge project.”

“It’s important to say that our focus is abolitionist,” Seigel said. “We’re not reformist. We are actually people who are involved in the fight to abolish the prison system.”

Episodes regularly call on listeners to do something tangible, whether that’s participating in a call-in campaign or sending letters and support to a prisoner who needs it.

In the second half of Episode 287, the audio quality improves. James Kilgore’s voice doesn’t have to come through a prison phone line like Espinoza’s did.

Kilgore is an activist and writer who was released from prison on parole in 2009, and Kite Line is airing parts of a presentation about the most recent of his five books — “Understanding E-Carceration.” It is rooted in his own experience of the electronic monitoring that was a condition of his parole.

E-carceration refers to all the ways in which technologies widen the net of the prison system, rather than providing an alternative to incarceration, Kilgore says. It targets people of color in the U.S. It tracks Palestinian youth in Gaza. Resisting it requires global solidarity.

“I also aim to do more than just describe,” Kilgore says of his book. “Hopefully, it’ll help mobilize people to push back against the expanding power of technology to punish and control.”

Meg March is a Kite Line volunteer based in New York City who contributes to the news at the top of each episode and conducts interviews to air on the show. Vast numbers of Americans live with a real and imminent threat that the carceral system could undo their life at any moment, March said.

Millions of people in the U.S. are currently or formerly incarcerated, and millions more know someone who is or has been incarcerated — according to a Cornell University study, 45% of Americans have had an immediate family member incarcerated.

“Kite Line holds an important space in that social context,” March said.

The show has a remarkable level of dedication and reliability, she said. It’s never missed a week.

As often as possible, Kite Line relies on first person storytelling by currently and formerly incarcerated people. Interview content is often driven by the interests of interviewees, and March and Seigel both said they don’t usually need to ask many questions.

“We just let them talk about what was important to them,” Seigel said.

Most of the time, their interviews with currently incarcerated people have to be done over the phone. But when the show began, Seigel was teaching inside the Indiana Women’s Prison and did in-person interviews with some of her students, a rare opportunity.

Soon after the show started airing in Aug. 2016, Beach set up her phone as a call-in line and encouraged people to pass the number around. As Kite Line reached a wider audience and began airing on more and more stations nationwide, the calls and voicemails from incarcerated people took over Beach’s phone.

“It’s such a Pandora’s box that if you have a heart, it’s really hard to not just keep receiving these calls and pleas and wanting to share these experiences,” Beach said.

Kite Line offers people on the outside a glimpse of what lives on the inside are like, covering a vast array of topics and experiences. It catalogs neglect, exploitation and indignity, but it also communicates the creativity and resilience of incarcerated people and the ways in which life continues behind bars.

“The state may rip you out of your own life, but you will create a new one,” March said.

The people who make Kite Line said they want you to know about the lives that are affected every day by the prison system. They want you to care about those lives. And most of all, they want you to do something about what you learn.

Back on Episode 287, James Kilgore says his book is a work in progress and that there is a lot more work to do. He says so much has already changed since he finished writing, but he hopes it will help inspire organization and resistance.

Just as Kilgore has finished describing his book and his goals, a siren interrupts Kilgore’s on-air conversation with the moderator, Ruth Wilson Gilmore.

“Sorry,” she laughs. “There’s always a siren somewhere.”

Kite Line Radio is a volunteer-run program and is looking for people to join their team. If you would like to help with prisoner correspondence, interviews, news or social media, send an email to kiteline@wfhb.org.