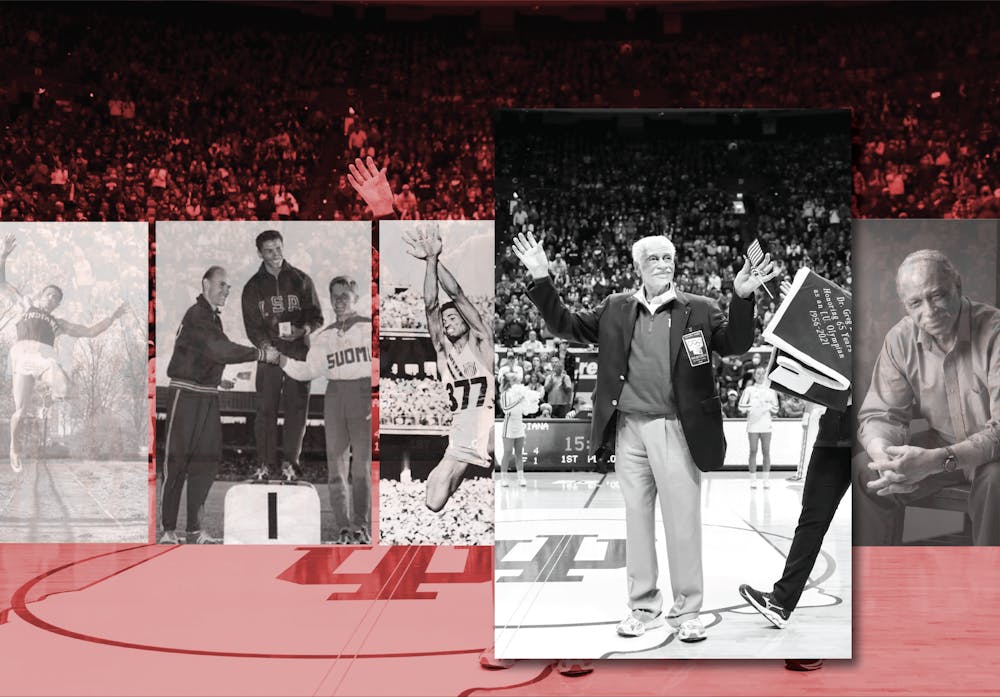

Greg Bell steadily made his way onto Branch McCracken Court at Assembly Hall, sporting a navy blue blazer with a square patch commemorating the 1956 Melbourne Olympics below the left breast pocket. His shoes, custom-designed, bore mementos from his past — the Indiana University logo, the Olympic rings, the American flag.

During the first media timeout of Indiana men’s basketball’s game against Nebraska on Dec. 4, 2021, Bell, holding an American flag with his white hair slicked back, looked out to a cheering crowd as he was recognized for his gold medal win in the 1956 Olympics.

The celebration mirrored the recognition Bell received nearly 65 years before. At halftime of the Dec. 10, 1956, game between Indiana and Butler University, Bell received a standing ovation at what is now the Bill Garrett Fieldhouse in honor of his gold medal, as written in a 1956 Terre Haute Tribune article.

Assembly Hall announcer Chuck Crabb introduced Bell before a video about his career played on the jumbotron. He was handed a crimson blanket, embroidered with white letters in recognition of his medal: “Dr. Greg Bell. Honoring 65 Years as an I.U. Olympian. 1956-2021.”

Brian Brase, the director of the I Association, Indiana’s letter-winning alumni organization that helped organize Bell’s ceremony, said Bell is a role model and magnanimous, larger-than-life figure.

Yet Bell doesn’t feel like he’s the legend IU is recognizing him as. In his own head, he’s Dr. Bell, the dentist who spent over 50 years helping patients.

“To hear people say such a thing as legend, that’s not how I see myself,” Bell said. “But it’s nice to hear.”

Bell didn’t plan to attend college at all, much less compete in long jump at IU.

If it wasn’t for a case of tonsillitis and subsequent treatment from a physician by the name of William Bannon, he might have spent the rest of his life working at an Allis-Chalmers factory producing machinery.

“I probably owe everything I am to this man,” Bell said.

Bell was drafted to the Army during the Korean War in 1950. While stationed in France, he competed in the European Championships where he won the long jump. He joined the Armed Forces team as a chance to explore the country and came back with a 1-foot-tall trophy.

When Bell returned home and came down with tonsilitis, his mom called Bannon to check on him. Bannon walked into Bell’s room, which he shared with three of his eight siblings, and saw the trophy.

“Get your ass out of that bed and go to school,” Bannon told Bell. “You have some talent.”

Bannon hounded Bell for over a year in an attempt to make him go to school. Finally, Bell agreed to try. He met with Gordon Fisher, then the track coach at IU, who told Bell he wanted athletes who wanted to compete and were willing to work hard. Bell joined the team.

Bell said Bannon gave him a $10 bill when dropping him off in Bloomington so he could buy a steak dinner. Bell, who came from a poor background, decided not to spend it all at once.

“I ate for over a week on that $10,” Bell said.

As a freshman, Bell didn’t receive much coaching other than his time running with the sprinters and practicing his jump, but he didn’t need much more assistance. Since freshmen weren’t eligible to compete at the NCAA varsity level until 1968, Bell had to sit out — despite having jumped 2 feet further than the rest of the competition.

Finally, in 1955, Bell competed in his first meet in Boulder, Colorado. He jumped 26 feet.

Bell became the fifth man ever to jump 26 feet, easily winning the competition and surprising a crowd that hadn’t heard of him before.

The start of Bell’s career preceded the success he would have while at Indiana. He was a three-time Big Ten Champion, a three-time All-American. He was ranked first in the world in long jump from 1956-1958. He won the NCAA National Championship twice, including in 1957, when he jumped 26 feet, 7 inches — an NCAA record that would stand for seven years.

In 1982, Bell was inducted into the IU Athletics Hall of Fame as part of the inaugural class. Six years later, Bell was inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame. He never lost a long jump competition.

Bell’s arrival in the dental industry was another stumble, he says.

While at Indiana, Bell decided to study within the medical field, but wasn’t sure what practice. Eventually he decided to try dentistry — the only field he was patient enough for, he says. With dentistry, he was able to see instant results he never could get in other medical fields.

Bell returned to his hometown in 1962 and opened a private practice. He quickly had a roster full of patients who knew him — and just as many who pretended to know him to get a discount.

In 1969, Bell decided to find a salary job. He took a position at Logansport State Hospital, where he worked until his retirement in 2020.

Bell was the first member of his family to attend college, and most of his siblings never graduated high school. His family was never well off, and Bell spent several years of his childhood living in a chicken house.

That time helped shape who Bell was: quiet, but driven and selfless.

“He knew what hard times were,” Hallie Bryant, a longtime friend of Bell and a former Harlem Globetrotter, said. “What other people thought was hard was easy to him because he really knew what hard times were about.”

Bryant, who played basketball at Indiana from 1955 to 1957 and toured with the Globetrotters for 13 years, said he met Bell at the Indiana Memorial Union when the two were in school and got along well. When Bryant was inducted into the IU Athletics Hall of Fame in 1998, they met up again and have talked weekly since. Bryant said he and Bell have similar life mottos: help where you can and hinder none.

At one point, Bryant told Bell, who was naturally modest, that the accolades he received were about more than just him, but about his family and his community too.

Now, at 91 years old and once again being honored, Bell’s mind is as sharp as ever, Bryant said, and he’s still helping others.

“We’ve both been blessed to still be here,” Bryant said. “We know our names, can count to two and tie our shoe. So we’re doing good.”

Bell was awestruck when he arrived at the Olympic Park Stadium in Melbourne, Australia, for the Olympic track and field events.

“I’m looking back on my history, and I asked myself, what is this little country boy from a small produce farm in southern Indiana doing here on another continent, assuming he’s gonna beat the best on this entire planet?” Bell said.

Bell only found himself in Melbourne thanks to, once again, Bannon’s insistence. Bannon, who had been following Bell’s career at Indiana, told him he’d see Bell in Melbourne for the Olympics.

“I thought, ‘yeah, that’s another empty promise,’” Bell said.

But Bell decided to try to qualify anyway. John Bennett, then a student at Marquette University, was the American frontrunner and had been unchallenged leading up to trials. Just like in Boulder in 1955, Bell came out of nowhere and quickly turned heads.

“The closest John Bennett ever came to beating me is we wound up in a tie in the Olympic trials,” Bell said.

On Nov. 24, 1956, Bell competed in the Olympics. The winds were gusting up to 30 mph, he estimated, and the athletes were petitioning the officials to let them jump with the wind rather than against it.

He strained a calf muscle on his first jump, which was just short of 23 feet. He decided he had come too far to pull out of the competition, so he returned for his next jump.

Bell jumped 25 feet, 8 ¼ inches — a distance which won him the gold medal by nearly six inches over Bennett.

“My jump, as far as I was concerned, was not a very good one,” Bell said. “It was just better than everybody else’s.”

That night, Bannon took Bell out for a steak dinner.

When Bell returned home after the Olympics, he saw a friend while walking on campus.

“It’s good to be back,” Bell said to him.

“Where have you been?” the friend replied.

Over the 65 years since, Bell has returned to campus plenty of times, both to be honored and to give back to the university. Bell was honored with the Z.G. Clevenger award — given to letterman alumni who have made outstanding contributions to Indiana University through service to its athletics program — in 1993, and he has returned almost yearly for the annual award dinner.

At this year’s dinner in September, Brase found out it was the 65th anniversary of Bell’s gold medal win.

“The wheels just started turning about how we could recognize that, and a men’s basketball game is always the best,” Brase said. “It was a very warm ovation he received.”

Bell won’t say it himself, but the crowd’s reaction when he took the court speaks to it enough: Bell is a legend.

“I see him as an Indiana University treasure,” Brase said. “We’re so lucky to be associated with Dr. Greg Bell.”

Now, Bell will sit at home in Logansport, Indiana, watching Olympians jump a foot farther than he ever did.

While the Olympics have changed in the 65 years since he competed, Bell still holds the values from those games. He doesn’t like that winners bite their medals. He also believes winners shouldn’t put their medals in a safe, hidden from the world.

Bell made a wooden case for his gold medal in the shape of Australia. When he visited IU in December, he brought it to show in case someone asked to see it.

“I don’t know how many thousands of hands have touched my medal,” Bell said. “I have a good friend who made a guesstimate that more hands have touched my medal than anyone else who has one.”

In his retirement, Bell isn’t as active as he used to be. He knows better than to challenge someone to a race now, but he’s far from immobile. Just over three years ago, Bell had just finished mowing his 4-acre lawn when his wife suggested downsizing their house. He says he caught her off guard by agreeing.

At his new house, Bell was sitting on his back deck, enjoying the weather. He’s not sure why the thought occurred to him, but he decided to check how long it was.

Bell decided to pull out a tape measure and checked. It was 26 feet, 7 inches — the exact same length as his best jump.

“Now how’s that for a coincidence?” Bell said.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article incorrectly named Bell’s tonsillitis.