Pick any of Kendrick Lamar’s first four studio albums and it’ll likely be the most ambitious rap album released that year. Beginning in 2011 with “Section.80,” Lamar’s projects have repeatedly stunned listeners with their vivid storytelling detailing his life and experiences.

Each album is a grandiose concoction of different sounds, incorporating poetry, jazz, hymns and other styles seamlessly into Lamar’s iconic prose. They’re full of extraordinarily bold set pieces, such as Lamar’s sobbing, gutted verse on “u” or the gunshots abruptly cutting off his speech in multiple of his tracks.

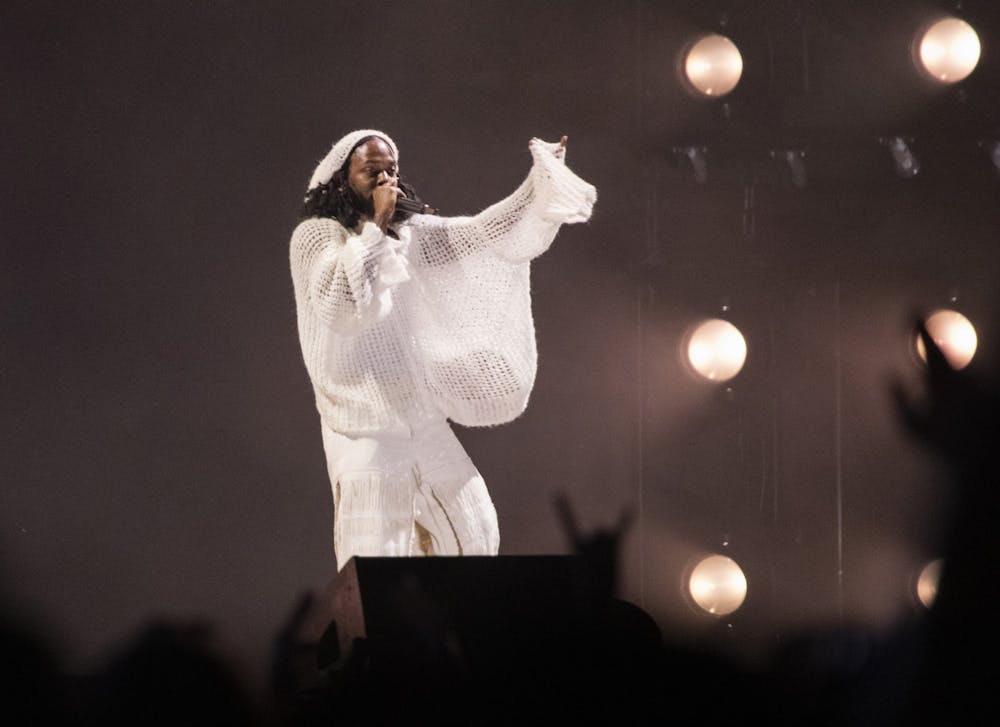

Lamar’s newest album, “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers,” loses some of the high-concept sound Kendrick Lamar has been known for, but retains the strong thread of ambition running through his entire body of work.

The opening track, “United in Grief,” is the most reminiscent of his previous music, running through several different sonic textures in its four minutes. It’s an excellent introduction, calling back to the classic Kendrick Lamar sound while bringing in the tone that will persist throughout.

“Father Time” features a beat alternating between sections of funky piano and bass and flute-led counterpoint, while Lamar discusses his relationship with his father and the generational patterns of toxicity these conflicts can create.

This intimate exploration of interpersonal conflict between family and community members can be heard in a number of other tracks on “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers.” “We Cry Together” depicts a fight between a couple that’s as lyrically impressive as it is viscerally uncomfortable, while “Auntie Diaries” examines the treatment of Lamar’s queer relatives.

Lamar’s music has always been very political and, as his audience has increased, so has his scope. His first two albums deal with life in his hometown of Compton, California. While these issues remained present in his third album, “To Pimp a Butterfly,” he began to take a wider perspective, which would continue in his fourth album, “DAMN”.

“Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers” follows this pattern in some ways, but mostly takes a step backwards. Lamar touches on widespread issues, but does so through an intensely personal lens.

On “Crown,” a consistent set of piano chords accompanies the repetition of “I can’t please everybody.” The title track, “Mr. Morale,” uses a harsh, minor trap beat to discuss generational trauma and abuse as seen in cases like R. Kelly. “Mother I Sober” features a similar soft piano texture with an understated bass drum sounding a heartbeat through verses that bare Lamar’s past experiences with sexual assault, which he delivers in a muted style until a grand, angry crescendo near the end.

Much of Kendrick Lamar’s music is able to communicate emotion to a remarkably vivid degree, but rarely has he taken a vulnerable position across an entire work like he does in “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers.”

There’s much to miss about this album on a cursory listen. As is par for the course when it comes to Kendrick Lamar’s music, it features incredible detail both lyrically and musically, much of which may not be immediately apparent. Many of the tracks draw in a fan of the genre immediately, but some require another listen or two to have the full effect.

“Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers” represents something truly novel in the world of rap, as has come to be expected from Kendrick Lamar. Especially with male artists, the rap genre is often dominated by an obsession with stoicism bordering on apathy. This album is uncharacteristically open with its subject matter, with Lamar giving the listener a deeper look into his personal struggles while retaining the signature style for which he is known so well.