Nicholas Almendares wants to make it clear that “money is the lifeblood of politics.”

It’s an old quote, and he’s not entirely sure who to attribute it to — if anybody at all — but it’s an accurate mantra nonetheless, he said, especially as running for office has only gotten more expensive for candidates.

“There’s some pretty good empirical support that money helps you win an election,” Almendares, associate professor of law at IU’s Maurer School of Law, said. “You think on a basic level, if I’m spending $10 million and you’re spending $0, they’re going to hear a lot more about Almendares.”

Although state candidates can often raise contributions numbering in the millions of dollars — Indiana Senator Todd Young, for example, has raised around $10.21 million in 2022 alone, according to OpenSecrets — local candidates are usually looking at amounts much smaller than that. But this doesn’t necessarily mean those contributions are intrinsically less valuable, Peter Iversen, a Monroe County Council member for District 1, said.

“People spend a lot of their time earning their dollars, and we know that people are hurting right now in this economy, that it’s really hard to part with those dollars,” he said. “If you can show a certain campaign has received a certain number of gifts, that it does show that there is viability in that campaign.”

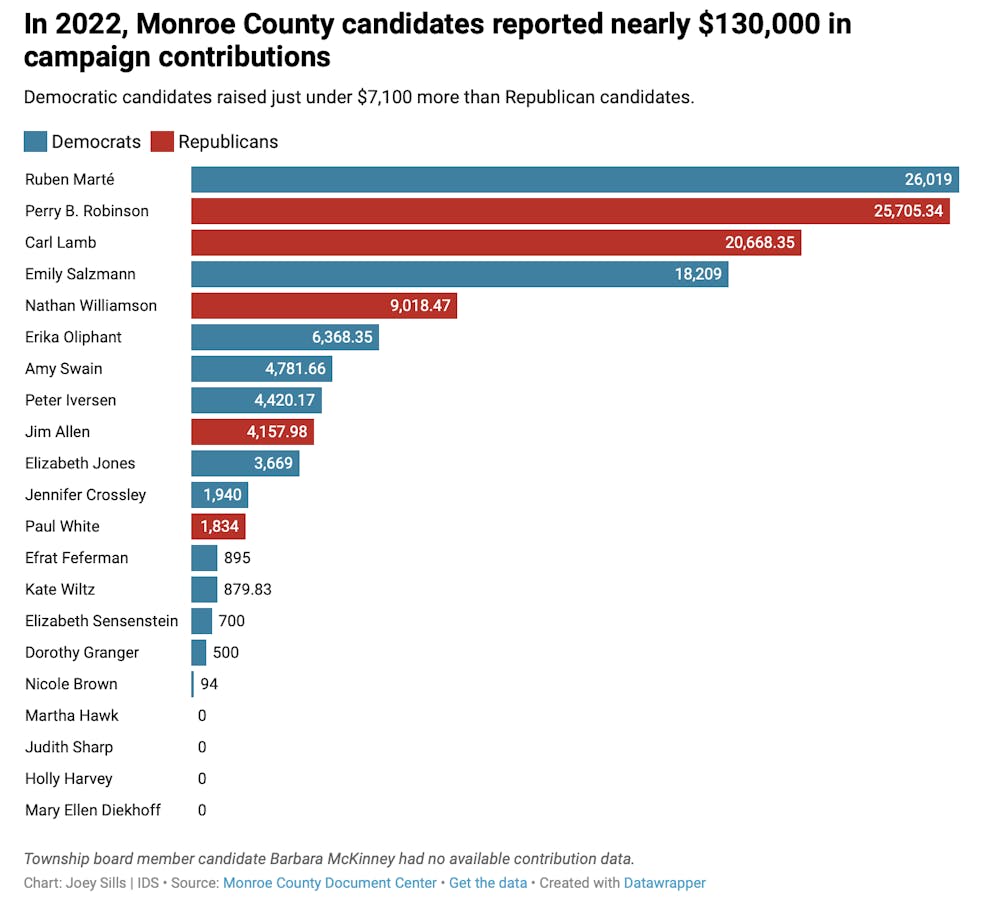

Iversen, a Democrat, said grassroots fundraising is especially important to him as a candidate, and the average donation to his campaign is $35. According to his pre-election CFA-4 form filed Oct. 21, which lists all itemized contributions and expenditures of his campaign or all those contributions and expenditures over $100, Iversen has raised roughly $4,420 during 2022. Of that number, about $2,265 is listed as unitemized, or less than $100.

Related: [Here’s how Monroe County voting really works]

If the number of contributions received by a campaign shows its “viability,” as Iversen said, then the public CFA-4 forms submitted by each Monroe County candidate in October present a clear picture of how each campaign is looking. They also provide key, though limited, insights into the spending priorities of each campaign.

Iversen said much of his expenditures are on field operations, including informational pamphlets to help with door-to-door canvassing efforts and yard signs. This is reflected in his CFA-4 form, where his campaign reported over $1,500 in expenditures to the Cobb Group, a commercial printing company based in Dayton, Kentucky.

On the other hand, other candidates, such as Martha Hawk, Monroe County Council member for District 3, report no outside contributions on their CFA-4 forms. Hawk, a Republican running unopposed, said she felt no need to ask for money because she has no competition.

“I know that people who have money to give to campaigns need to put it where they think the money will do the most good,” Hawk said.

Hawk also said there is an advantage to having name recognition. Having served on the Monroe County Council since 1988, she said most people simply assume she’ll win anyway and won’t need the cash donations; nevertheless, she said, her strong local presence means she’s historically spent very little time actually asking for contributions in the first place.

“When I have opposition, I don’t even need strategy — they just show up with the money,” she said. “I’m local. I’ve been here; people know me. People trust me. And, if they see opposition, then they just pitch in and they want to make sure that I get in there.”

Campaign finance, on a federal level, is regulated by the Federal Elections Commission, an “independent regulatory agency charged with administering and enforcing federal campaign finance law,” according to the FEC’s website. The FEC only has jurisdiction over those running for the U.S. House of Representatives, Senate, and the presidency and vice presidency.

Since the establishment of the FEC in 1974, the Supreme Court has issued several decisions greatly modifying campaign finance regulation, most notably in the 2010 case Citizens United v. FEC. In this case, the court ruled corporate funding of independent political media could not be regulated, according to Ballotpedia — in other words, political spending by corporations and other organizations for candidates they haven’t coordinated with may not be regulated because such spending is protected by the First Amendment.

“If you just want to take out an ad that says, like, I don’t know, ‘J.D. Vance is awesome’ or ‘J.D. Vance is the devil,’ you just choose to do that,” Almendares said about the candidate J.D. Vance, who is running for the U.S. Senate in Ohio. “You don’t talk to J.D. Vance. He doesn’t know you — you can just do that, and there’s no limit on that.”

Related: [How Indiana candidates for U.S. Senate have talked about IDS readers’ top issues]

This is where political action committees come in. According to OpenSecrets, PACs are political committees organized for the specific purpose of raising and spending money for and against candidates. Super PACs, on the other hand, are those PACs with no formal connection to a candidate — they are therefore permitted to raise an unlimited amount of money from individuals, corporations and other organizations, granted that money doesn’t go directly to the candidate, according to OpenSecrets.

With super PACs come “dark money,” a term that essentially refers to donations coming from an unknown source. According to Campaign Legal, nonprofit organizations aren’t required to disclose their donors so long as politics aren’t their “primary activity.” These organizations then contribute to super PACs, which in turn informally work to elect a particular candidate, according to OpenSecrets.

However, for local and state candidates, campaign finance laws vary from state to state, with differing contribution limits and candidate reporting requirements. In Indiana, individual contributors and PACs aren’t limited in how much they can donate to any campaign, according to Ballotpedia.

One of the hurdles that comes with being a local candidate, Iversen said, is the fact many know very little about local offices compared to the state or federal offices on their ballot. For Iversen, asking for contributions has been just as much about education as it has been about donations.

“Our name recognition isn’t as high as some of those races that are higher up on the ballot, and the actual statutory duties that we are charged with aren’t so well known either,” he said. “So, we go through and we kind of help educate people on what those statutory duties are.”

Iversen, who was voted to fill a vacant seat left by former Councilwoman Shelli Yoder in 2019, said this is the first time he’s felt the need to raise funds to help defeat an opponent from the other side of the aisle. Hawk, a veteran councilwoman of over 30 years, has spent no money on her campaign at all. Both agree, as politicians, on the fundamental importance of campaign finance, especially for local candidates.

“The big thing is that politicians believe it helps. We have testimonials from them, typically X politician saying, ‘We need campaign money,’” Almendares said. “They spend a shocking amount of their time raising money. It’s a huge chunk of what they do — so, they think it’s important.”