We set out for Terre Haute early in the morning. I had been up deep into the night writing, but I wasn’t tired — I was eager to visit the old comrade’s house. We stopped for a milkshake breakfast — I’ve been prescribed an ice cream diet after getting my wisdom-teeth removed — and then began the long drive south from Portage.

The morning had been dispiriting to say the least. Waking up to learn the Supreme Court said it was cool for Christians to discriminate against queer people but not cool for the president to relieve crumbs of student debt, while not shocking, somewhat hampered my enthusiasm for the day trip.

I wanted to visit Eugene Debs’ house because of my socialist politics; my mother came along because she teaches fourth grade and wanted to learn some more Indiana history for her students (and because she’s a good mom, I suppose).

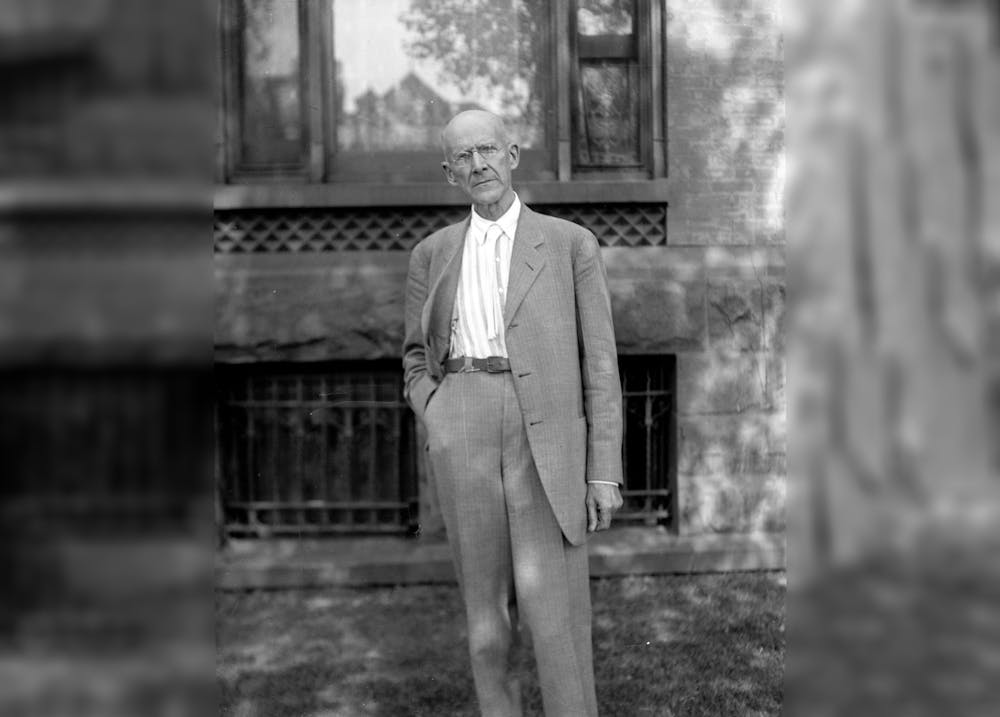

Before Bernie Sanders revived the socialist movement in this country, Debs was America’s most famous socialist. He founded the American Railway Union in 1893, cofounded the American Socialist Party in 1900 and ran for president five times. He received nearly a million votes — a little over 3% of the popular vote — from his prison cell in Atlanta in 1920.

Debs was imprisoned in 1918 for violation of the Espionage Act — he was critical of the U.S. government and the imperialist war it was fighting in Europe. For his courage in speaking against a predatory capitalist war on behalf of the working poor who fought in it, he was jailed. His 10-year sentence was eventually commuted by President Harding in 1921.

Today his house in Terre Haute is a museum. The fairly large, Victorian-style home he shared with his wife was built in 1890 and has a long history — before it became a historic landmark, it housed a fraternity from 1948-1961 at Indiana State University. I was thankful the frat boys hadn’t burned the house down.

[Related: OPINION: Prisons are obsolete]

Debs was criticized in his day for the house by his opponents and some who would otherwise have been allies. It was apparently a little bourgeois for someone who purported to speak on behalf of American workers. But as Deng said, poverty is not socialism. Debs lived in a nice house, but that’s not a fault, nor a contradiction of the socialist worldview — we believe everyone to an extent should have the opportunity to enjoy the finer things.

My mother and I were lucky to have a tour of the house. Our guide, a lovely comrade warm and knowledgeable, informed us that most of the city was without power because of storms the night before and wasn’t sure the museum would be open when the day started.

Others would join us later, but for half of the tour we were one-on-one with the guide who made Debs feel alive and relevant, mixing his story with spirited political conversation about capitalism, prisons and war.

Debs has lost none of his vitality in a world rife with inequality, brutal prisons and imperialist wars. He writes in his memoir, “Walls and Bars,” that socialism will eliminate the need for prisons. When we entered the library, the guide drew our attention to an ornate table, the centerpiece of the room, that wasn’t originally in the house. It had been crafted over a century ago by one of Debs’ friends and fellow inmates who was a carpenter.

That table speaks volumes about Debs’ philosophy — even the lowest prisoners, the “wretched of the earth,” have something valuable to offer to society. Debs hated prisons because they degraded humankind. The table, beautiful and still standing, is a testament to human resistance.

I won’t go over everything that happened that day, like my awestruck face when I saw Debs’ personal copy of “Capital” which led to his conversion to socialism during his first stint in prison, or our time in Debs’ guest room where people like Upton Sinclair once stayed. You should go there for yourself and see, especially if you’re a leftist.

Being at the Debs house filled me with hope and inspiration. Debs is defined by his courage. Marx long ago called on us socialists to “openly, in the face of the whole world,” publish our views, aims and tendencies. In red-scared America it would be easy to hide that we’re socialists; it might even be individually beneficial. Espousing socialism invites controversy from every corner, but Debs was never afraid to speak out and did so at great personal cost.

While I was at the Debs house I thought about Republican Senator and Voldemort lookalike Rick Scott, who recently said socialists and communists were not welcome in the state of Florida. At first, I just laughed, thinking about telling my brother I couldn’t attend his wedding in October because I’d been barred from entering the state.

[Related: OPINION: What we can learn from Karl Marx, the journalist]

Thinking more about it, I realize how lucky I am because of Debs. He is an example to all socialists. We shouldn’t be afraid of reactionaries like Scott — we must boldly oppose them, we must stand by our convictions, we must never lose our faith in the people.

Faith in the people is crucial. Debs said he wasn’t a Moses-figure who could lead the people to socialism — if someone could lead the people to the promised land, someone else could lead them out. It is ultimately the workers themselves who will bring about radical change. What we should take from Debs, each and every worker, is his courage, his willingness to struggle.

Like Moses never saw the promised land, Debs never saw socialism — may he forgive me for the comparison. But I know we will get there eventually. A world without exploitation, without prisons, without war. Eventually we’ll get there.

Jared Quigg (he/him) is a senior studying journalism and political science.