At age 17, my part-time job in a local restaurant had become a sanctum. I clocked in looking forward to contently hustling alongside a hodgepodge, yet inextricably tight band of coworkers, and making light conversation about endless topics with a never-ending stream of customers. I was energized by the delicious aroma of food and pastry, always plotting the best time to slip into the kitchen and chat up the staff for my free meal. It was a thing of beauty, to watch a strip plaza hole-in-the-wall restaurant unite people of all kinds in a dinner rush.

And then there’s the other side of it: like the man who colloquially came to be known to my peers and I not by name, but by cocking our chins, looking at each other with leering eyes, dropping our voices low and saying "Thank you, baby” in a crude imitation of his favorite three words.

"Thank you, baby” was an older man who sauntered into the restaurant during its slowest hours, when few tables were occupied, and our manager was conveniently on his mid-afternoon lunch break. "Thank you, baby” liked to wave you over for a water refill and hold you there for several minutes, professing your beauty and weaving an elaborate narrative about how if he was a producer, he’d turn you into a big, Hollywood star, but shamefully he’s not; he just has millions in the bank from some other, lamer thing. "Thank you, baby” liked to caress wrists, elbows and shoulders. In the past, you’d figured you wouldn’t let a customer like him slide. In the future, you’ll tell friends the story of a crotchety regular and his audacious passes for laughs. In the moment, though, you send a panicked look to your coworkers for help as his hand snakes around your waist, his breath heavy on your neck. No one moves. You all wonder the same:

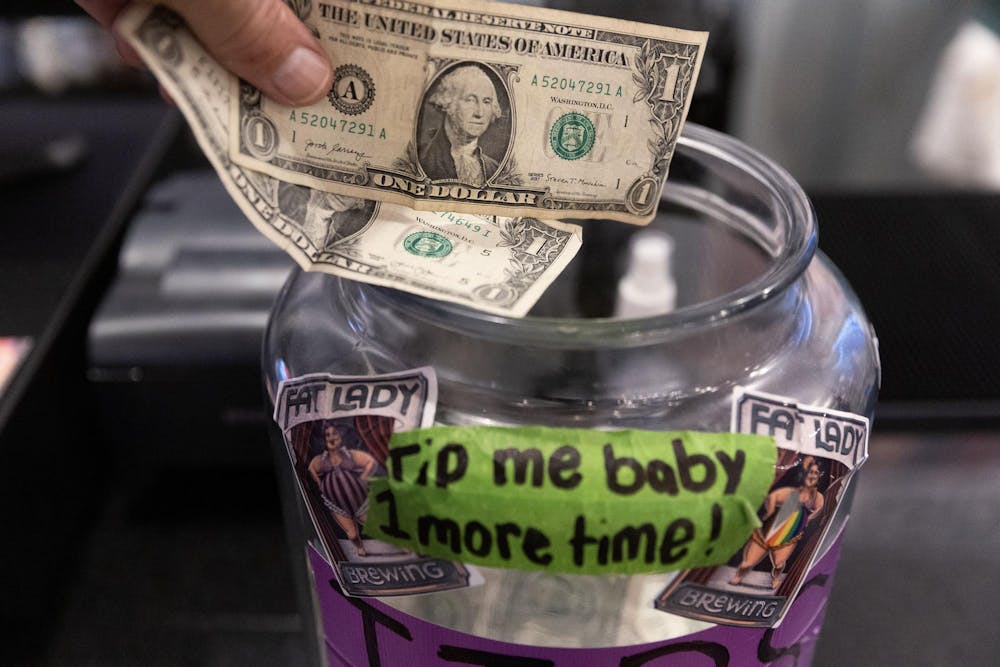

If I move away, does he get angry? If he gets angry, will he not tip?

Kindred experiences are prolific for female restaurant workers — even more so for those who are tipped. A 2017 report published by the Restaurant Opportunities Center United, a nonprofit organization for worker’s rights, reveals the findings of a study conducted with Forward Together, a reproductive justice organization. Almost 90% of tipped female restaurant workers have experienced some form of sexual violence in the workplace, and those for whom tips amount to the bulk of their income are twice as likely to be harassed as women working in states without a tipped sub-minimum wage.

Though the Fair Labor Standards Act has presently set the federal minimum wage at $7.25 an hour, exceptions for tipped workers have been in place since the FLSA was first established in 1938. As the ROC United report details, restaurant workers were initially excluded from the act entirely before an amendment in 1966 established a sub-minimum wage for tipped workers —50% of the full minimum wage. Although the minimum wage has risen through the years, lobbying by the National Restaurant Association — who spent over $1 million on the practice in the fourth quarter of 2023 alone — has kept the tipped subminimum wage frozen at $2.13 an hour since 1991. It remains there for many states, including Indiana.

In a statement to the Washington Post, a spokesperson for the National Restaurant Association refuted any correlation between tips and sexual violence, but research doesn’t support that conclusion. Academics at the University of Nebraska found that “the mere expectation that a female worker is compensated with tips could induce sexualized perceptions of her and make sexual harassment appear more legitimate.” Analysis of reports filed with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found that accommodation and food services recorded the most sexual harassment claims filed of any industry.

The report published by ROC United further revealed that over a third of tipped workers who left their jobs cited sexual harassment as the reason. With their salaries on the line, female workers are pressured to weather frequent degradation and sexual violence from customers.

In abolishing the practice of tipping and subminimum wage, restaurant workers can gain stability without risking their safety, health, and dignity. Until then, my peers and I have marginally reclaimed these losses by finding a sense of ownership and pride in working earnestly for a cause — for me, that manifests in a proclivity to boast about “my restaurant.”

My restaurant serves divine food; carefully curated ingredients and recipes culminate in Thai food that fills you with warmth, wood-fired Neapolitan pizza that indulges your deepest cravings and tres leches cake that balances your palate after a savory meal. My restaurant is staffed by the kindest, most hard-working people: cooks who come up with new taco flavors every month, dishwashers who safeguard the back end, pastry chefs who prep from the early hours of the morning, bartenders who mix up a mean Shirley Temple (it’s what keeps me going) and servers who cultivate a marvelous atmosphere. My restaurant draws in people from all around the state, even from all around the country, and joins them in lines that tumble out of the front door.

But as has become customary in the business, my restaurant also draws in regulars like "Thank you, baby” — and I find it quite impossible to take pride in that.

Ellie Willhite (she/her) is a freshman pursuing her BFA in cinematic arts with minors in sociology and Korean.