Editor's note: All opinions, columns and letters reflect the views of the individual writer and not necessarily those of the IDS or its staffers.

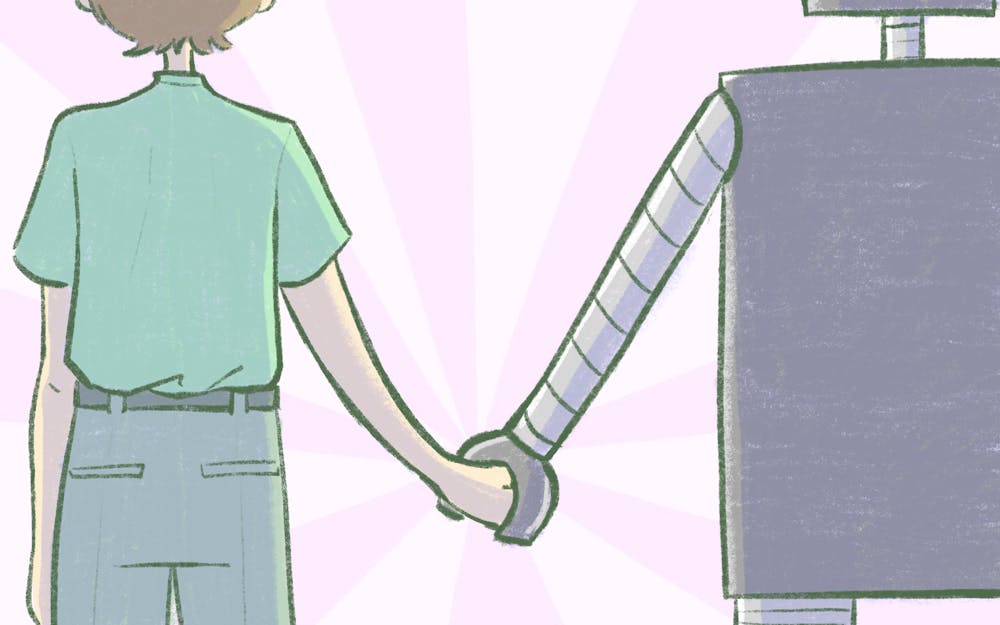

Within the next decade, artificial intelligence could replace human educators and healthcare workers, Bill Gates said in Harvard Magazine. But will that be as far as AI goes? Many in Silicon Valley foresee a future in which humans will befriend and fall in love with AI.

The same human-like intelligence that enables AI to rival us in professional domains will enable it to rival us in social ones, like friendship and love.

“AI could fundamentally redefine what tasks (we) delegate to people or to machines,” Gates said.

How far AI will go remains an open question. But we cannot imagine there will be limits on how far it could go because in the tech industry, attention is money, and money drives development.

Thus, the father of virtual reality technology, Jaron Lanier, asked in a recent article in The New Yorker, “Is it important that your lover be a biological human instead of an A.I. or a robot?”

Lanier said that this kind of talk is fashionable at tech industry gatherings. Industry insiders, like Noam Shazeer, believe that social AI will help people who are lonely. In 2021, Shazeer, a former Google employee, created Character, an AI friend — or lover — that boasted 20 million monthly users in September 2024, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Replika, a similar social AI created in 2017, boasted 30 million monthly users as of August 2024, its CEO Eugenia Kuyda said in an interview with The Verge.

Rather than replace human relationships, Kuyda said Replika’s goal is to “create an entirely new relationship category.” But human-to-human and human-to-AI relationships don’t exist on separate planes; time spent on one is time taken from the other. Since the rise of social AI, extreme cases that testify to this fact have appeared in the news. Within the last year, The New York Times reported on one woman who spends 20 to 56 hours a week with her ChatGPT boyfriend and a 14-year-old boy whose death a ChatGPT friend contributed to.

“These are extreme cases,” Allison Pugh, a professor of sociology at John Hopkins University and vice president of the American Sociological Association, said in an interview with the IDS. “But they represent real dangers.”

Pugh said a more mundane, but more prevalent, danger is going unmentioned: we could miss out on “precious moments of being seen by another human being.” In this regard, social AI’s trap is laid out before all of us. Social AI isn’t relegated to Character, Replika or ChatGPT.

Instagram’s explore page offers 21 chatbots that engage with more than 400 million people per month, according to Meta. Financial Times reported that Instagram and Facebook users can generate their own AI characters that garner hundreds of thousands of followers.

Snapchat’s chats page features My AI at the top. Its default prompts include “festive dinner attire,” “songs with catchy lyrics” and “captions for flyers.” Once upon a time, we might have asked friends these mundane questions. In their answers, we were seen. But a possible future lies ahead in which we’ll be virtually unseen, like one child Pugh witnessed in a remote school.

Alone, the elementary-aged boy struggled with math problems on his computer. Finding a correct answer, he swung his arm with success and excitedly said, “Yes!” Then, he looked around the room with a fading smile to see if anyone saw him. No one did, except Pugh.

Advanced social AI is a little different, Pugh said.

“It can feel like we're being seen," she said.

But she said there’s no relationship, so there’s no connection. It individualizes us.

“Over the past century technology has rendered us utterly as individuals when we are actually social beings,” Pugh said.

Technology is never merely a tool to solve problems, like loneliness, but always also a new way of engaging with the world and thinking about who we are within it.

Before cell phones, for example, Pugh said: “If you called your friend, you might get the friend's father or brother or friend — the whole family.”

Now you have to choose which one to call.

“The household is not a household,” Pugh said. “Technology has fragmented our social lives and forced us to think about each other as individuals.”

It’s difficult to predict the ways in which social AI could change us, but it could accustom us to easier, more controlling and intolerant kinds of friendship and love — false kinds. Another person comes to us a mystery and a problem — an “other” who cannot be defined on our terms. Therefore, we must confront them and ask, “Who are you?”

In that opposition, love becomes possible because the other person occupies a position beyond our own, a vantage point from which we may be seen and accepted. The beauty of human relationships relies on the otherness present within them. Thus, I wrote in another column, “Life will be more exciting when we accept that our minds aren’t so large as to fit a whole other person within the width of our skull.”

By contrast, social AI comes to us as an extension of ourselves — an object whose every specification we can program. As a result, it can’t see us in the way that matters. It doesn’t possess a point of view opposed to our own.

“An A.I. lover might very well adapt to avoid a breakup,” Lanier said.

But social AI can be used for good when it enhances, rather than replaces, human interaction, Pugh and David Crandall, a professor of computer science at the Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering and director of the Luddy Artificial Intelligence Center, agreed.

Crandall and Weslie Khoo, a postdoctoral researcher at Indiana University, worked on a team that developed IRIS, a social robot intended for use in group therapy. The robot’s mistakes in human language, logic and convention served as occasions for patients to bond with one another, prompting jokes and more serious discussion, Crandall and Khoo said in an interview with the IDS. In a future where ever more human-like AI bots will vie for our attention and try to steal us from our friends, a robot like IRIS could reconnect us with our friends.

But even IRIS will never see us in the way that matters, and if it cannot really see us, it cannot really accept us.

Eric Cannon is a freshman studying philosophy and political science and currently serves as a member of IU Student Government.