Editor's note: All opinions, columns and letters reflect the views of the individual writer and not necessarily those of the IDS or its staffers.

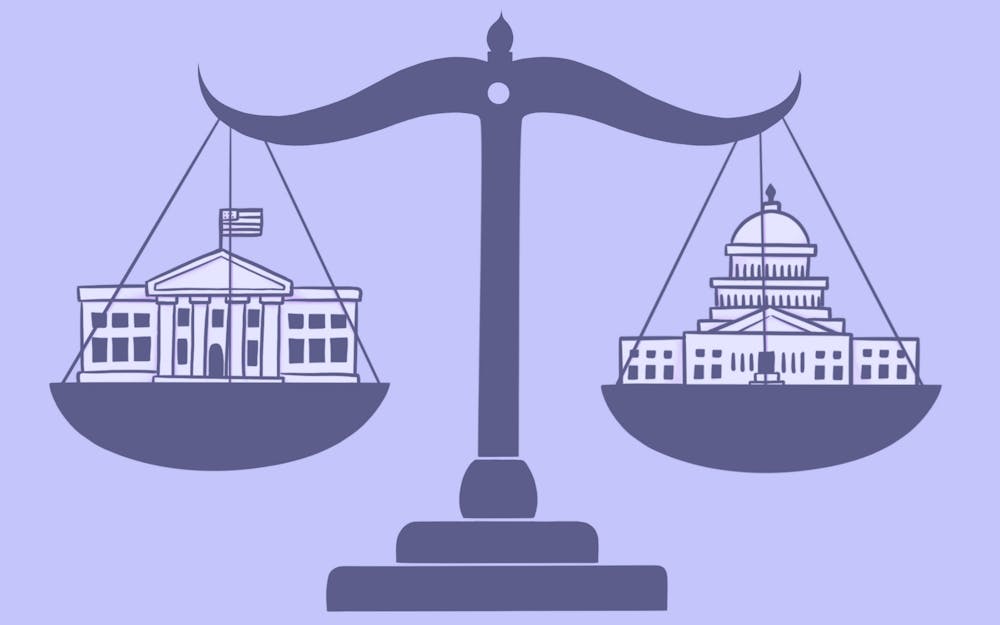

President Donald Trump signed 137 executive orders in his first 100 days. Over the same time, Congress passed two bills. A “do-nothing Congress” is the norm. With each administration, more executive orders than bills reach the president’s desk. As such, Trump’s second term does not represent an aberration but the most recent (and natural) evolution of the U.S. government. While presidents once deferred to Congress’s agenda and then needed Congress to assent to their agenda, Trump shows that we have entered the age of the do-it-all president.

In week one of office, Trump signed 10 executive orders on immigration, deportation and border security. Since then, more than 1,200 “international students ... have had their visas revoked or their legal status terminated,” including at Indiana University. In some cases, this occurred without “justification, notice, or due process.” Additionally, around 250 people have been deported and imprisoned in El Salvador without due process. This occurred by executive fiat in what one federal judge has ruled contempt of court orders to reverse the deportations.

“We cannot give everyone a trial,” Trump responded on social media. “To do so would take, without exaggeration, 200 years.”

Throughout history, presidents have used — or concocted — crises to extend the power of their office. In fact, the presidency itself arose during a crisis.

After the Revolutionary War, the U.S. government was solely comprised of a legislature.

Some founders were “wary of putting power in one person’s hands,” Andy Rudalevige, a professor of government and legal studies at Bowdoin College, said in an interview with NPR. However, uprisings against state governments, British soldiers on American soil and a national legislature that couldn’t enforce its laws called on a single figure of authority to emerge.

While this notion initially met silence from delegates to the Constitutional Convention, Rudalevige said they eventually accepted it: “The executive power shall be vested in a president of the United States of America.” But they marked all presidential powers, from making treaties to appointing judges, with an asterisk: “By and with the advice and consent of the Senate.” As it turned out, this restriction on presidential power also acted as the kingmaker of presidents.

“All the president really needed in order to expand that vaguely defined power was buy-in from Congress,” Rudalevige said in the article.

And buy in Congress did. While Washington often “deferred to the Senate in his decision making,” subsequent presidents stretched their powers during crises, setting new precedents. In 2019, Trump claimed, “Article 2 allows me to do whatever I want.”

Then, he wanted to fire agency heads; today, he wants to control the agencies. Remember, the Roman emperor Caligula also said, “I can do whatever I want to whomever I want.” Appointed by President Ronald Reagan, Justice Antonin Scalia’s decisions laid the groundwork for an imperial theory of the presidency. Touted by the Heritage Foundation, this theory justifies Trump’s strongarming federal agencies to execute laws as he deems fit, even in defiance of the courts.

For Trump, the presidential office does not chiefly execute Congress's will but voices woes and advocates policies; it is a “bully pulpit.” Although associated with President Theodore Roosevelt, this term describes the presidency as construed by Andrew Jackson and every president since Franklin Roosevelt. In 1828, Jackson won the election after a narrow defeat in the previous cycle. This election marked the first time that all white male citizens of the U.S. could vote for president. As a result, Jackson “cast himself as the people’s tribune” with a mandate to defend them “against special interests and their minions in Congress.” He waged a war on the national bank, moving funds into state banks without congressional approval.

Later, President Franklin Roosevelt perfected the art of the bully pulpit. In 1933, Roosevelt’s New Deal marked the first time that a president proposed a comprehensive plan to Congress for it to implement. Over the course of the Great Depression and the Second World War, he used radio to convey his ideas directly to the American people. New technology allowed the president to become a spokesperson during the country’s crises. Through them, Congress deferred to the president. After them, it allowed Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon to wage wars during the Cold War without its approval.

In 1973, historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., traced this expansion of power to Richard Nixon, then its climax, in his book, “The Imperial Presidency.” At issue for Schlesinger was the president’s power to make war, a power granted to Congress in the Constitution. Although Congress declared war on neither Vietnam nor Cambodia, Nixon continued war on the former and invaded the latter. Today, neither Congress nor the Constitution has authorized Trump’s war on immigrants. Unfortunately, history has taught Congress to play second fiddle to the president.

There is no going back to 1789. In many ways, that’s undesirable. It's also not possible. The evolution of the presidency cannot be isolated and reversed. It is too entangled with all other modern developments: technologies like radio and television have irreversibly changed the way we regard presidents. Schlesinger advised us that a modern president is needed for a modern world — a world where innumerable issues call for someone to look at them and discuss them. There’s no turning around. But a president isn’t meant to be an elected absolutist whose court includes two chambers of jesters. There is going forward with a Congress that knows self-confidence and answers executive power with its own power as the people's branch.

Eric Cannon (he/him) is a freshman studying philosophy and political science and currently serves as a member of IU Student Government.