Editor's note: All opinions, columns and letters reflect the views of the individual writer and not necessarily those of the IDS or its staffers.

The phrase "flooding the zone" was adopted in 2018 by former Trump White House chief strategist Steve Bannon. It describes a strategy aimed at overwhelming the media and American public with so much information that it is impossible to keep up. This strategy of distracting us with the noise was often successful in Trump's first term.

Though Bannon first embraced this tactic in 2018, Trump’s current administration has used it even more in its first three months than any other president. By the end of January, Trump had signed 46 executive orders, already a quarter of what he signed during his first term, and a third as many as Biden signed during his entire presidency. These executive orders range from attacking transgender rights and ending diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives to threatening law firms and issuing blanket tariffs on foreign nations. He also signed an order banning paper straws.

This rapid-fire approach to executive orders is key to the “flooding the zone” strategy. By issuing so many directives so quickly, the administration ensures each action gets lost in the shuffle, creating a sense of urgency and chaos. This prevents a thorough and measured response to policy decisions, saturating the conversation and keeping opponents on the defensive. It also takes time to mount legal opposition to each order.

Executive orders are just one way Trump, and his allies flood the zone. Equally egregious is the Trump administration’s rhetoric. Think about it: within the last three months, there's been discussion of making Canada the 51st state, of Trump serving for an unconstitutional third term and annexing the country of Greenland.

This is rhetoric you'd expect to hear from authoritarian countries like modern-day Russia or Germany during World War II and not from the United States of America. The scary part is that you can't be entirely sure if they are serious or not. For example, Vice President JD Vance visited Greenland with the message that they join the United States even though Denmark has told the U.S. numerous times that it isn't for sale. In a poll commissioned by two Danish and Greenlandic papers, 6% of Greenlanders said they think the island should join the U.S. In the survey, 9% said they were undecided. It is hard to know if this is a serious threat, but we need to pay attention to it all the same.

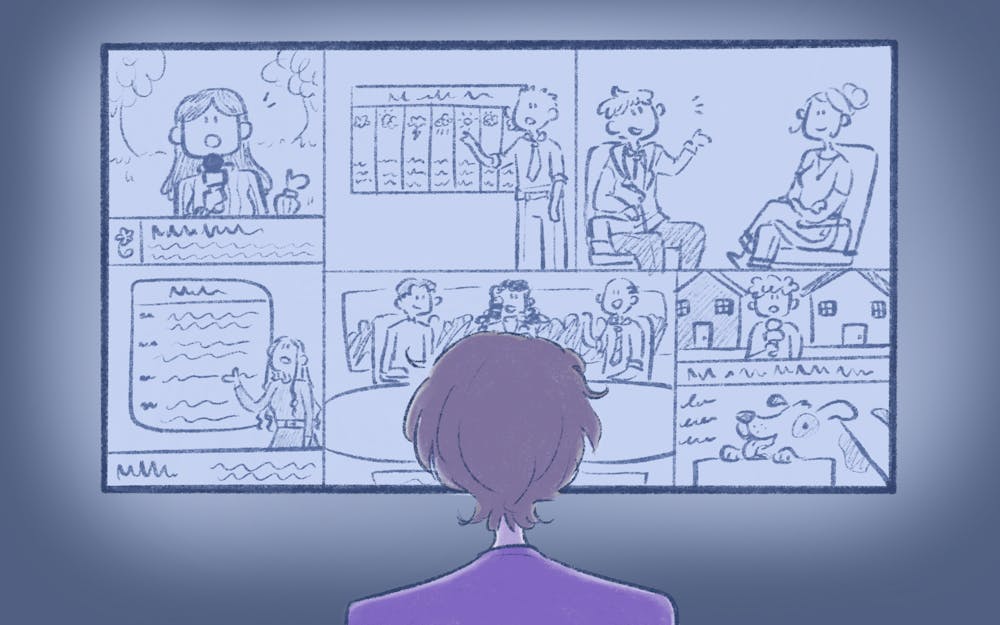

The challenge is knowing whether what the Trump administration says is a real plan or a distraction from other issues. Like in baseball, how do we know what balls to swing at? The media must better inform the public about the issues and help filter out daily garbage. The news of the day needs to be acknowledged, but not all actions and statements should be given equal weight or airtime.

The media can help us distinguish between what is consequential and what could be a distraction. Journalists should focus on providing context and analysis, digging deeper into possible motivations and implications, rather than just amplifying the actions and rhetoric of whoever is in power. For example, with the current situation in Greenland, I see a lot of news organizations giving too much credence to the idea this is a real possibility even though Greenland and Denmark have both said it’s not for sale. For updates on this situation I’ve followed NPR because I feel it does the best job providing the information but also acknowledging the craziness of the claims being made by the Trump administration

Fostering an environment where the public is media literate is essential and a responsibility, we all share in a democracy. According to Boston University, nearly 75% of Americans believe being media literate is important but less than 50% of citizens know where to find that training.

Promoting media literacy can empower the public to know what a reliable source is and what may be misinformation. Media literacy shouldn’t be a rare skill to find; rather it should be the norm. Media literacy education can be delivered in all aspects of our lives through schools, public programs and the government. The training could include how to evaluate your sources, recognize our own biases and detect possible misinformation.

IU Media School professor Kamady Lewis said the best thing the media can do is hold the powerful responsible.

“Being a journalist isn’t about being liked or not liked, right?” Lewis said. “It’s about the truth, and we always say you can not like the facts, but it doesn’t make it not true.”

But it can’t just be the media holding the powerful accountable. Every citizen has to participate, pay attention and speak out, or no substantial change will be made. It can be scary to call the powerful out, but it becomes less frightening if we all do it together. We have to keep our eye on the ball to know where to swing.

Jack Davis (he/him) is a sophomore majoring in media and pursuing a minor in folklore and ethnomusicology and a certificate in journalism.