The picture didn’t look too out of the ordinary. A couple bats, scattered gloves, maybe a hat and a pair of cleats. Standard for a college baseball locker.

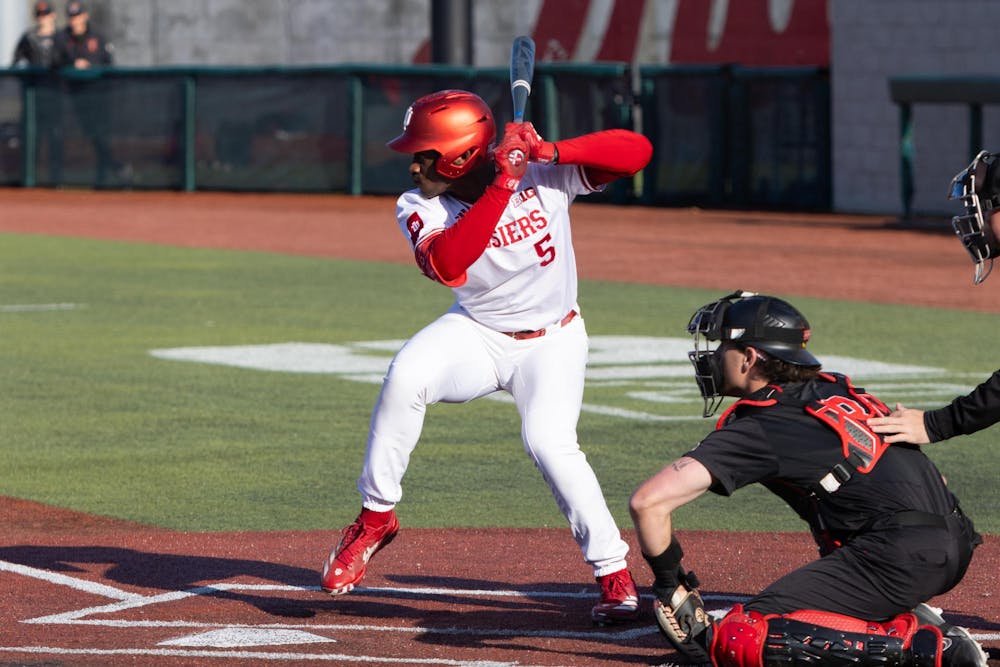

Devin Taylor, then a freshman at Indiana, sent his father a text with the image of his cubby. It took Carey Taylor some time to realize what his son was really showing — the crimson nameplate with the No. 5, which he’d chosen prior to the fall season.

Carey’s younger brother, and Devin’s uncle, Chris, died from a rare blood infection in the fall of 2011. Devin doesn’t have vivid memories from then, but he remembers their Nerf gun fights. Carey remembers the playful wrestling.

Chris Taylor played college baseball at Kentucky State University and joined Carey, who played at Thomas More College, on an adult travel softball league. On the Saturday morning his health started to sharply decline, the team had a World Series qualifier in Orlando.

The following Wednesday night, he was gone.

His number while playing? Five.

“My main thing is family,” Devin said. “Once they call the number five, I just think I’m doing it for him.”

When Chris Taylor was on the field, his energy was infectious. Carey can’t remember many times his younger brother wasn’t smiling. He’s always seen a similar joy in his oldest son. It’s easy to spot, that wide grin in left field or in the dugout.

“That’s his happy place,” Carey said.

***

Inside Indiana’s clubhouse, just to the right of a ping pong table, leftover Chipotle bags are ripped and sprawled across the counter. “Heathens,” head coach Jeff Mercer says as he disposes of the trash. He swaps his baseball pants for blue jeans, cleats for brown cowboy boots. The wall behind him reads “History Happens Here,” and “Only 659 miles to Omaha.” He slumps onto a couch and spits into a green plastic Gatorade cup. He continues to spit between sentences.

Mercer is an intelligent man. He speaks eloquently and says things like “dichotomy” and “ingenuity.” He’s also uniquely capable of connecting with players on a personal level. Mercer was the lead recruiter in the charge to sign Devin Taylor, once a 14-year-old phenom in Cincinnati.

He was first tipped by Jordan Chiero, one of Mercer’s assistants at Wright State University, about a lanky outfielder with an approach to hitting that mirrored an MLB veteran. Mercer caught his first glimpse of Taylor at the Junior Future Games at Grand Park in Westfield, Indiana. He was taking a phone call when Taylor led off the inning, and he saw the eighth grader lace an extra base hit on the first pitch he saw.

Mercer remembers his “huge feet and huge hands” barreling around first base.

“He looked like Fred McGriff,” the coach said.

But then they started talking, and Mercer noticed more than he could’ve imagined. He saw maturity and empathy and sensitivity and awareness. He saw a kid who shrugged off social media and attention in a social media and attention-dominated world.

Taylor’s mother and father were always present for recruiting calls with Mercer. So too was Taylor’s younger brother, Chandler, who, unbeknownst to his family, would sometimes be lying on the floor on the other side of the room, listening in.

They rarely talked baseball. Mercer indulged Taylor about ping pong games against his father. “We’d talk trash to each other,” Carey said. They talked about Taylor’s basketball games at La Salle High School, especially his buzzer-beating three to top St. Xavier in the 2020 district finals. They talked about Mercer’s fishing endeavors and Taylor’s school classes.

Mercer never badgered Taylor about updates on his commitment decision.

“It wasn’t just a robotic call every time,” Taylor said.

Mercer’s acutely aware of how harmful the spotlight can be on highly touted youth athletes. Money is at the forefront of everything. Players are pulled in countless directions, an autograph here, an appearance there, endorsements everywhere. Mercer noticed early in the recruiting process that Taylor saw those as trivial — tangential, at best, to his ultimate goals of winning and making it to professional baseball.

Throughout high school, Taylor became a bonafide star. He ranked as the second overall player in Ohio and the 19th best outfielder in the country. Those who watched him drew comparisons to Ken Griffey Jr., who played high school ball just over 20 minutes away from La Salle in the 1980s.

Taylor never paid that any mind.

“Devin never changed,” Mercer said. “He was never loud or boisterous in a way that brought attention to himself.”

***

Carey Taylor isn’t sure how his son first got into puzzles.

He wasn’t engrossed with them as a kid, he knows that for sure. But last season, as a sophomore, Taylor was known to play Sudoku on bus or plane rides. He’s since ditched the numerical puzzles for coloring books and jigsaws.

Nothing too specific, he says. He’ll go to Goodwill and make a beeline for the puzzle section, spending $4 on a few 1,000–1,500-piece sets. He sits around the house working on them for hours. One puzzle takes him about two weeks to complete.

“Everybody else is on Instagram,” Lance Durham, Taylor’s longtime hitting coach said. “He didn’t care about the ‘being cool’ part.”

Durham, the head baseball coach at Fairfield High School in Fairfield, Ohio, said he never had to “hold his hand.” There were sessions where Durham didn’t utter a single word in the batting cages. And if he had a critique, perhaps about being too picky on borderline strikes, he never had to say it twice.

He sees much of his old self in Taylor. Durham is the son of two-time MLB All-Star Leon “Bull” Durham and starred at the University of Cincinnati before bouncing around the minors for a few years. On April 29, 2009, Durham hit a home run against Xavier that traveled an estimated 550-560 feet.

Both Durham and Taylor grew up as decorated athletes in the Cincinnati area. Both swing lefty and throw righty. Both learned so much about life, about relationships and about baseball, from their fathers. Durham wears a size 14 shoe. Taylor sports a 15.

“We’re really kind of the same person, and that’s what I noticed in him from a young age,” Durham said.

Early in their training together, Durham begged his father to come watch Taylor hit. At the time, Taylor was 14 years old. The elder Durham watched in awe. He saw unbelievable polish and acumen, an almost masterful approach to swinging the bat. But through the years, it wasn’t Taylor’s contact skills or plate discipline that impressed Durham the most.

During group hitting sessions, Taylor could be on the receiving end of some wisecracks from his peers.

Devin doesn’t hang out.

Devin doesn’t get girls.

“Devin would just sit there like, ‘I don’t care,’” Durham said. “Somebody told that kid that all that stuff’s going to be there when it’s necessary, and he believed it. I knew that his head was straight.”

Durham said Taylor would’ve skipped his high school prom to hit the batting cages. A harmless exaggeration, maybe. But Taylor, standing with his arms crossed near the dugout at Bart Kaufman Field, said he didn’t go to prom.

“I probably did hit that day,” he said with a chuckle.

Once Taylor arrived at Indiana his freshman year, that focus and drive only intensified. He could hit and play a solid left field, but he was skinny. “175 pounds soaking wet,” Mercer said. Taylor adopted an extensive regimen with Chris Virtue, the team’s Director of Athletic Performance.

He ate the food. Lifted the weights. Taylor found a mentor on the team in Phillip Glasser, who’s now playing Double A in the Washington Nationals system. Glasser used his final year of collegiate ability to return to Bloomington, and Taylor committed himself to following the veteran around and mirroring his work ethic.

Every morning at 10 a.m. sharp, Taylor would join Glasser in the cages. When Taylor wasn’t in class, he’d lift weights or work on his swing. Mercer noticed that he never skipped steps — he attacked the process with an insatiable desire to improve. Taylor ultimately added around 30 pounds to his frame and unlocked a powerful swing that transformed him into one of the nation’s top hitters.

As just a freshman, Taylor hit .315 and belted 16 homers. The next year he batted .357 and smacked 20.

Really, none of it should’ve been surprising. Four times a week growing up, sometimes more, seldom less, Taylor and his father would head to the Winton Woods High School field just around the corner from their house to hit. When he was 10, he’d field ground balls and practice swings with Carey’s softball team, some of whom were former professional players.

Carey Taylor thought it was odd, seeing how completely devoted and attached his son became to baseball. He loved the sport, loved winning, but nothing like this.

“You could tell that Devin was not interested in all the extracurricular stuff,” Mercer said. “He wasn’t interested in the social life, he wasn’t interested in partying. He just wanted to be a great player.”

***

During a game at Northwestern in Taylor’s freshman season, there was a promotion at the ballpark for youth baseball players. Mercer estimates around 50 of them swarmed Taylor after the game, asking for autographs on their hats and a quick photo.

Nineteen years old. Celebrity status. Taylor smiled and obliged, chatting and taking a genuine interest in conversations.

Roughly 15 minutes before an early April win over Ball State this season, Taylor was signing baseball cards and explaining to a fan why he wears No. 5. He divulged the intimate details.

Mercer thinks long and hard when trying to describe Taylor’s legacy. One of the program’s finest talents, sure. But there’s much more. He ponders the question for 42 seconds and scratches his beard. No spitting.

“Time is our most precious, valuable commodity,” Mercer said. “Money is so far down on the list compared to other attributes of our life that make a real difference. Devin values those things. People appreciate that and they love him for it.”

Taylor himself doesn’t quibble with things like legacies. Those are abstract and form well after he’ll have accomplished what he hopes to. He feels the same way about expectations.

Do those do anything to improve his swing? Improve his fielding?

He didn’t worry about them as a star 14-year-old with an entire state — and sometimes region’s — eyes set on him. He didn’t mind when scouts flocked to his games, furiously scribbling on their clipboards and intently tracking his performances. He didn’t feel any added pressure when he was first thrust into Indiana’s lineup, or after becoming the Big Ten Freshman of the Year, or hitting 20 homers his sophomore season or becoming the program’s home run king as a junior.

In a few months, Taylor is expected to be a first-round pick in the MLB Draft. Assuming he leaves for the pros, he already plans to take online classes and finish his degree in sport marketing and management. He’s soaking in college life now, enjoying his walks along Kirkwood Avenue, enjoying his training and enjoying spending time with his teammates.

He can worry about everything else later.

“I always stay where my feet are,” Taylor said. “I always think about the future when that day comes. I never just skip forward."